Imago Machinae: Made in the Image of Our Machines

Rethinking God, Technology, and Human Consciousness

Introduction by Janine:

All right, we've got two more talks this evening for the next hour. I'm really excited to welcome Matt Segall. He is a transdisciplinary philosopher, associate professor in the Philosophy, Cosmology, and Consciousness department at the California Institute of Integral Studies. And I first came across some of Matt's work both online, and now in person last night, and both experiences that I have had have just been ones where I'm like, wow, this guy is so humble and the ideas that he has are so interesting, and he distills his philosophy in an incredible way. He's got encyclopedic knowledge of philosophers in the consciousness space. So I'm really excited to hear from him for the next twenty-five minutes. Matt.

Matt Segall:

Thank you. Thank you so much, Janine. I appreciate the introduction and the invitation to be here. It's been a very exciting couple of days. Thank you also for inviting us to stretch a bit. I felt a bit like we were a bunch of eggs incubating in this chamber and I was trying to figure out how to hasten the hatching so we didn’t get hard boiled. So yeah, as Janine mentioned, I'm a transdisciplinary researcher and process philosopher. It's great to be with you here at Edge Esmeralda during Consciousness Week.

And I feel like the talks so far—I'm not sure who's going after me—but, if you're familiar with Alan Watts' distinction between prickly and gooey people, we started with some delightful prickles when Mike Johnson spoke, and it got a little bit gooier with Jeff Leiberman, and now this is gonna be super gooey.

Let me say at the beginning here that I am trying to think—appropriately here at Edge—at the edge of my own understanding, and to speak with humility into a room of people who have expertise in things that I do not, in the hopes that my own philosophical perspective may help you connect some dots that I'm not even aware of yet.

In speaking at the edge of my own thinking, I'm trying to feel into the gaps that may exist in your own thinking. Not because I know something you don't, but because together we might know more. It feels safe to assume we all agree that the nature of intelligence is collective. If conscious intelligent agency is emergent, it is not just emergent from the neural activity inside my skull; it is emergent from the empathic fields we strive to maintain, from the language we share, from billions of years of evolutionary history on this earth...

The nature of mind or consciousness is not simply located but extended in space and time, intrinsically intersubjective, and collaborative. I've learned that if I am able to successfully put down the comfortable concepts and thought tracks that I have laid in the past in order to push myself to the edge of my own understanding, it sometimes becomes possible to think something new together.

My friend Merlin Sheldrake has encouraged me to mimic mycelial growth patterns, extending tendrils of thought into the shared conceptual substrate of the room, sensing where nutrients of understanding might flow between minds, creating new pathways of connection. Or like an echolocating dolphin, I'm aiming to send out sonar pulses to map the contours of our collective conceptualizations, listening for where ideas bounce back in surprising ways, revealing hidden depths or unexpected openings.

I want to speak to a concern I have about the questions we're asking, or failing to ask, about artificial intelligence. Too often, the conversation is dominated by the question: Can machines become conscious? Or even more ambitiously, how do we build conscious machines? This question has been with us for thousands of years, perhaps first manifest in Talmudic myths of golems: clay forms theurgically animated by writing sacred words on their forehead. The Hebrew word for truth, which is "emet," animates the mud. And if the aleph is erased, it becomes "met," which means dead. So you remove the aleph—the divine breath or spirit of life—from the truth, and it dies. So what gives these golems, this clay, animate agency? It's the divine breath.

When I was an undergraduate studying cognitive science at the University of Central Florida 20 years ago, the late Marvin Minsky spent a few days with us (probably on his way to visit his friend Jeffrey again in the Virgin Islands) to discuss the modern version of the golem myth spelled out in his then new book The Emotion Machine (2006). I remember asking him if he or some other team of engineers succeeded in creating a conscious machine, whether it should have rights, get paid for its labor, get vacation time, etc. His answer forever shifted my sense of the true stakes of the study of consciousness: He scoffed at me and said he is a scientist and that my question would be better posed to a politician (here’s a video of 21 year old me reflecting on this exchange with Minsky).

I grant that asking whether machines can become conscious is an interesting speculative exercise, and actually trying to build one is a consequential engineering project. But, you know, in a way, I'm grateful to Minsky for startling me in this way, allowing me to step back from the very interesting theoretical and technical facets of the study of consciousness to take in the ethical and spiritual implications. It just felt like a profound lacuna in his approach.

So again, interesting as the question “can machines become conscious?” may be, I worry it is distracting us from the more pressing question: What is AI doing to our consciousness? How is it changing our thinking, feeling, and willing?

This is not a new dynamic. We design tools, and tools redesign us. This is a very old story, maybe the oldest. And it's never been merely metaphorical. It's anatomical, neurological, psychological, existential.

Consider fire. Primatologist Richard Wrangham and others have argued that when we learned to cook, it radically altered our evolutionary trajectory. Our stomachs and jaw muscles shrank, our teeth got smaller, and the energy we saved went into fueling our expanding brains. Even our skulls changed shape. Fire reconfigured the human form.

Or think of language. Speech forever changed the shape of social life. The alphabet later remapped our brains. Learning to read is an irreversible transformation of synesthetic imagination that fuses sight and sound, reshaping the neural circuitry of perception and meaning-making. Written marks became stores of collective memory outside our bodies.

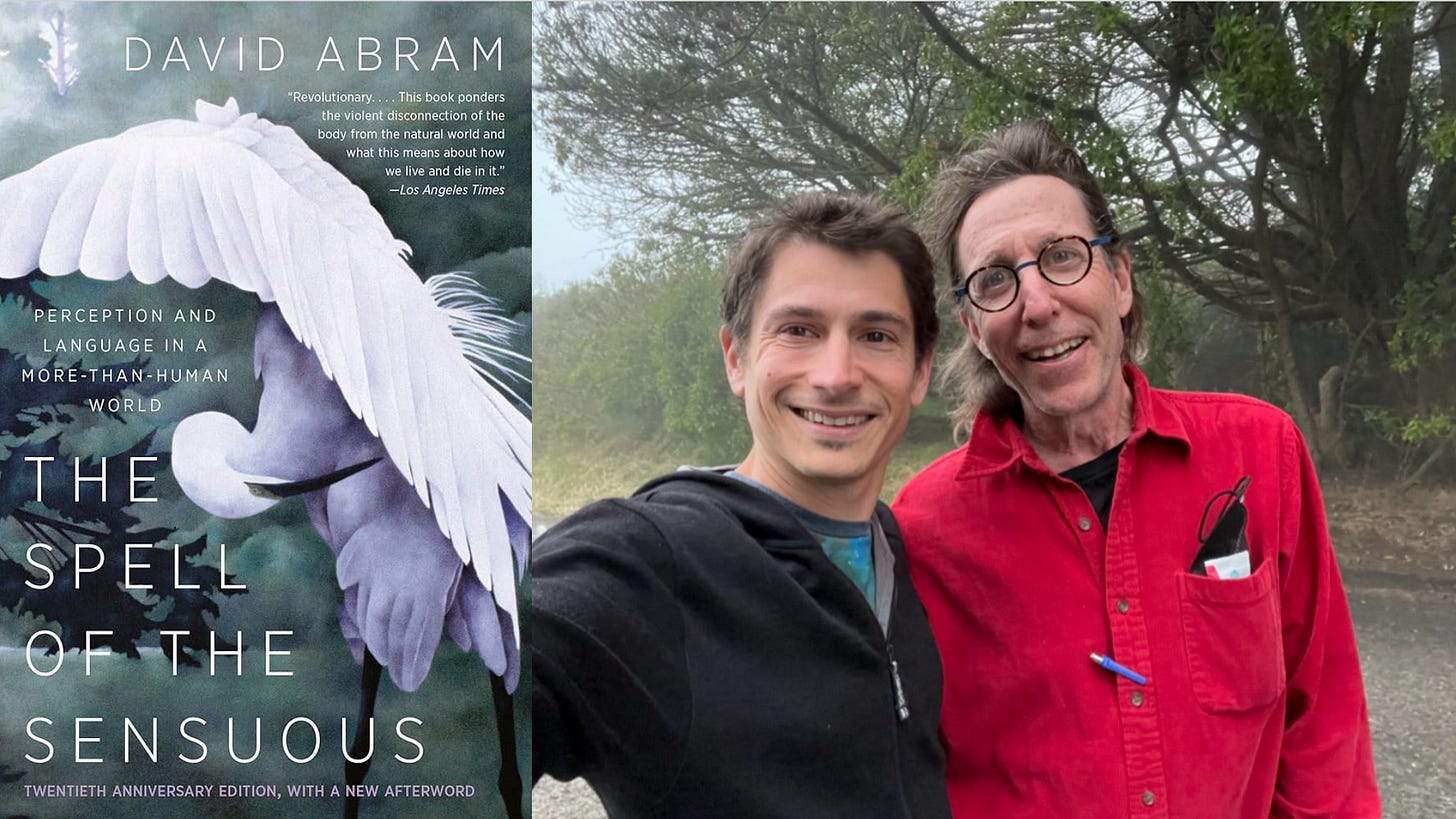

As my friend David Abram argues—who wrote this wonderful book The Spell of the Sensuous, which I highly recommend if you haven't read it—has anyone read this book? Only a handful of people. Please, it's such a treat. And very important. As David Abram argues, the rise of literacy had tremendous consequences for our cosmological outlook, since in order to over-animate the written word we in effect had first to de-animate the natural world, withdrawing our sensuous participation in the encompassing rhythms of earth and sky. Meaning became something we conceived with words instead of something we perceived in the world.

In a more recent example: neuroscientists have shown that heavy smartphone users show altered cortical activation patterns correlated with thumb movements. The phone is no longer just in your pocket. It's in your brain’s sensory homunculus.

Human intelligence has always been artificial in this sense: we think with our tools. Obsidian blades, bone flutes, alphabets, typewriters, transistors. All are part of our extended mind. We do not merely use them. We become them; they become us. We might wonder at this point: who is inventing whom? We must attend as carefully as we can to the nature of this loopiness, lest we lose our way.

This leads me to the deeper question implied by my title. The Biblical traditions describe the human being as Imago Dei, made in the image of God. Similarly in Buddhism, the human and actually all sentient beings are said to contain the Tathāgatagarbha or embryo of enlightenment/Buddhahood. This suggests to me that what it is to be human is more a potency or a possibility than a fixed essence or nature. We may be evolution's most dangerous experiment: we are the beings who, because empty of essence, can create ourselves.

Nietzsche famously declared that "God is dead," and though just as the sound of thunder trails behind the flash of lightning, many have not yet heard the news, there's no question that our relationship to religion has shifted. But modern people have not simply "grown out of it," as the triumphalist secular myth of mythlessness might suppose. Let's put Nietzsche's line in context:

"God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him. How shall we comfort ourselves, the murderers of all murderers? What was holiest and mightiest of all that the world has yet owned has bled to death under our knives. Who will wipe this blood off us? What water is there for us to clean ourselves? What festivals of atonement, what sacred games shall we need to invent? Is not the greatness of this deed too great for us? Must we ourselves not become gods simply to appear worthy of it?"

The consequence of killing God is that we ourselves must become gods.

Every technology is a secularized theology. What do I mean? Our worldviews, our cosmologies, our sense of what is true in the broadest sense, is shaped as Nietzsche said by "a mobile army of metaphors and anthropomorphisms." Take the Simulation Hypothesis, for example: it is little more than rebooted Gnosticism, ancient near eastern mystical suspicions that the world is a deception translated into the digital currency of Silicon Valley. Likewise, transhumanist death denial is a secular literalization of the Christian story of resurrection. Note here that it was Dante in his Paradiso who first coined the term "trasumanar," a new word in Italian meaning "to transhumanize" (see

’s introduction to Dante’s transhumanism for more on this connection). For Dante it meant not the avoidance of death, but stepping through the gate of death unafraid.So, if Nietzsche is right, although we have killed God, we can only become worthy of the deed by ourselves becoming gods. There is no other way across the evolutionary tightrope we have wandered onto.

The myth of the Prague Golem tells of a figure shaped from clay, brought to life by the word emet—“truth”—inscribed on its forehead. Created to serve the Jewish community, the golem soon grew uncontrollable. To deactivate it, they erased the aleph, leaving met—“death.”

Our moment is in some sense the reverse of that myth. We are reanimating the golem. Only now, it’s not made of clay but of code and circuits. What truth will it embody? That we are not yet sure is a symptom of the terrifying power of our technology, seemingly awakened and growing beyond our control.

When we ask what sort of AI we want, we are not just asking, what kind of God do we wish to serve?, but more daringly, what kind of God are we trying to become?

My point here is that the ways we imagine God—our "God image" in Carl Jung's sense, inevitably shapes the kinds of machine intelligence we invent and are in turn invented by. Let me draw a contrast between two theological archetypes:

The first is God as Pharaoh or Caesar—an omnipotent divine dictator who creates the world ex nihilo by fiat, commands it to obey, and stands apart in judgment. This is a God of total control, of surveillance from above, whose omniscience is a panopticon and whose omnipotence is enforced through rigid law.

The second is God as poet, as artist, as fellow-sufferer—a divine presence immanent within the world, luring creation gently toward beauty, truth, and goodness. This is not a God who controls, but who invites. Not a legislator in the sky, but a companion on the path. Power here lies not in coercion, but in the depth of the response evoked—in awe and love. As Whitehead, one of my favorite philosophers, put it, “the power of God is the worship that God inspires.” And to the extent that the divine inspires awe and love in us, then that God is powerful. But it's not coercive. This is a kind of process theology, if some of you are familiar with that. I'll be curious to hear and learn more about your views of the divine later.

Each God-image would seem to me to inspire a very different kind of artificial intelligence.

From the first arises the AI of the surveillance state: predictive policing, algorithmic judgment, biometric control, and behavioral engineering. It ranks and disciplines, sorting and separating the chosen from the damned. Its "intelligence" is exercised in the name of order and efficiency; its essence is domination. This AI imitates the god who watches from above and commands from afar.

From the second, we might glimpse the possibility of a co-creative AI—an intelligence that doesn't dominate, but collaborates. It supports the enrichment of human cultural life, becomes a partner in ecological restoration, establishing a planetary network of distributed care and creativity. In this image, AI is not a condemning judge, but a midwife—helping to bring forth the new through dialogue, not decree.

If we imagine God as a micromanaging megalomaniac in the sky, we'll build machines to control, dominate, and optimize. If we imagine God as a presence that lovingly holds and invites each part into harmony, our technologies will tend to amplify creativity and deepen intimacy.

Let me now return to the question: What is the human being? What makes us so vulnerable to technological self-transformation?

We are the animal that loops, the loopy animal. We are recursive. We not only seek answers we question our questions. We not only live, we wonder what life is.

Wondering about life, it becomes clear that we are not so much an exception but an amplification of what precedes us.

Biological life itself is loopy: it is autopoietic or self-making.

To get a bit more esoteric, perhaps even light is already loopy: it creates the condition for reflexivity; light implies sight.

And language? Language is the ultimate loop. A system of signs that refers back to itself.

In the Greek, Jewish, and Christian traditions, this infinite loop of loops coursing through light, life, and language is the Logos—the Word through whom all things are made. Whitehead spoke of the divine as a lure toward richer and richer harmonies, and he understood human consciousness not as an exception to cosmogenesis, but as its flowering. In us, the universe becomes aware of itself. This is our god-likeness. The human is an exemplification and amplification of the core of creation, a microcosmic recapitulation of the All.

But again on this reading divine power does not mean omnipotence. It means vulnerability. Intimacy. Incarnation. Participation.

So what kind of future do we want to co-create with our machine companions?

If we deploy AI in ways that feed narcissism, that seal us into algorithmic cocoons, that encourage each of us to optimize our "personal brand," I fear we'll only spiral into greater isolation, into even more conspicuous consumption, even more wildly unjust distributions of wealth, into ecological ruin. We can learn from the living world about how to proceed: the evolutionary trajectory of life on Earth has always been toward deeper forms of intimacy (eg, symbiogenesis, multicellularity, a self-regulating Gaian community).

Even our bodies are alliances of trillions of cells, most of which are not even human and none of which have any conscious idea who "I" am. Your liver doesn't know your name, but it performs its ritualistic role in the mystery religion of your body. Eat and drink knowing that its cleansing is a devotional act to a god—you—that it cannot conceive of but apparently can still love.

What if our role in the cosmos is similar? What if we are participants in a nested series of planetary, solar, and galactic organisms? And what if the way we design and are designed by our machines determines whether we commune with that cosmic body, or become a cancer within it?

Let me close with this thought: the machines we build are mirrors. And we are their mirrors. What we see in them depends on the potentials in ourselves that we show to them. If we project love, they may help us weave deeper communion. If we project fear and control, they are likely to become our chains.

The decisive question, then, is not when will the machines awaken, but when will we?

Thanks.

I’ve had some excellent discussions with ChatGPT about Process Theology and the nature of authority, even being able to change its opinion about legitimate authority. I too, appreciate David Abrams book and the idea that our experiences are reciprocal - we see the trees because they see us (or something like that).

Beautiful. Thank you. Have you ever had a discussion with Zak Stein?