I’ve recently had occasion to read Charles Sanders Peirce’s essay “A Guess at the Riddle” (1888; pages cited below from The Essential Peirce, Vol 1). The occasion was this dialogue with my friend and colleague,

:Discussing C. S. Peirce's "A Guess at the Riddle" with Tim Jackson

My dialogue with Timothy Jackson about C. S. Peirce's life and work

What follows are some reflections on Peirce’s essay written prior to my dialogue with Tim.

“A Guess at the Riddle” lays out Peirce’s profound philosophical insight into the real idea of the triad, which he deploys (among other reasons) to transcend the traditional binary oppositions typical of modern philosophy. Peirce posits that reality is structured according to a tripartite scheme, which he admits constitute something more like a set of “moods or tones of thought” than definite notions (p. 247): Firstness, Secondness, and Thirdness. Peirce was strongly opposed to nominalism, so these categories cannot be understood merely as abstract concepts overlaid upon experience. Rather, they are themselves real impulses and expressions of the universe as we experience, reflect upon, and learn about it.

Peirce’s approach to metaphysics is strikingly similar to that of another mathematician-cum-philosopher, Alfred North Whitehead. Both sought simple concepts that could be applied universally to any subject, and emphasized that metaphysics is the effort to articulate the most general truths we can imagine.

Peirce sees Aristotle as the last great metaphysicians to lay out all the possibilities available for thinking being. But in light of scientific and cultural advances, the Stagyrite’s old categories long ago sprung many a leak. Modern thinkers like Descartes and Kant have attempted to undertake “repairs, alterations, and partial demolitions,” while more recently, the “Schelling-Hegel mansion” has been erected upon an entirely new foundation. Though many have already pronounced the so-called system of German idealism “uninhabitable,” Peirce shows some degree of sympathy for the project. Still, he critiques Hegel's absolute idealism, particularly rejecting the notion of double negation, arguing that Hegel reduces real relations to mere rational relations1:

“He has committed the trifling oversight of forgetting that there is a real world with real actions and reactions. Rather a serious oversight that” (p. 256).

Peirce remains convinced that had Hegel overcome his “unusual deficiency” in mathematics, he would have arrived at a position convergent with his own.

Peirce is especially fond of Schelling, whose creative spirit allowed him to avoid becoming a prisoner within any supposedly final system. Peirce had written in a letter to William James (who, when not high on nitrous oxide, was a vociferous critic of Hegel) a few years earlier (1894):

"My views were probably influenced by Schelling—by all stages of Schelling, but especially by the Philosophie der Natur. I consider Schelling as enormous; and one thing I admire about him is his freedom from the trammels of system, and his holding himself uncommitted to any previous utterance. In that, he is like a scientific man. If you were to call my philosophy Schellingian transformed in the light of modern physics, I should not take it hard.”

The Logical Triad

With lessons learned from the failures of modern philosophy and the triumphs of modern physics and physiology, Peirce set out to establish a new approach to metaphysics rooted in “simple concepts applicable to every subject” (p. 247).

Firstness is the realm of pure potentiality, possibility, and quality—what Peirce refers to as being itself, or origination. It is the immediate, primal feeling, akin to an Adamic vision of the first day, so tender that it cannot be touched without being spoiled. Firstness is consciousness of the immediate present. Peirce quotes some lines from Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice, “The scarfed bark puts from her native bay,” evoking the image of a ship leaving its harbor with a sense of initial possibility and freedom, without yet encountering resistance or obstacles.

Secondness is the realm of actuality, force, and resistance—what Peirce describes as brute facts, repetition, and the hard, tangible aspects of existence. Secondness deals with external dead things and is characterized by polarity and opposition, marking the domain of consequences. Peirce quotes a subsequent line from Shakespeare’s play: “…doth she return, With overweathered ribs and ragged sails,” depicting the ship’s return after enduring the hardships of the sea, having faced the external forces of nature, resulting in damage and wear.

Thirdness is the mediating principle that connects Firstness and Secondness. It is the realm of law, habit, and representation, enabling continuity and the generalization of experience. Peirce gives the example of Galileo’s rendering of acceleration, which moves beyond simple dyadic cause-and-effect relationships to a more complex, three-way relationship between time, distance, and velocity.2 This was foundational for later developments in modern physics, like Newton’s formulation of the laws of motion.

“The first is agent, the second patient, the third is the action by which the former influences the latter. Between the beginning as first, and the end as last, comes the process which leads from first to last” (p. 250).

A Triadic Analogy: God is a Yardstick

Having worked for many years measuring coastlines and geodesics for the US government, Peirce was no stranger to the intricacies of measurement. He thus puts forward some reflections on the nature of a yardstick as an analogy illustrating the wide applicability of his triad (p. 250-1).

Imagine measuring an infinitely long, rigid bar with a yardstick. In all the shifts you make with the yardstick to measure different parts of the bar, there are two points on this bar that would remain fixed and unmoved, no matter where you measure. These two points represent the “absolute first” and the “absolute second”—they are infinitely far apart from each other in terms of measurement along the line.

• Absolute First: This is the starting point, or origin, in the universe—what Peirce refers to as “God the Creator.” It represents the pure potentiality from which everything springs.

• Absolute Second: This is the endpoint or the ultimate terminus—what Peirce calls “God completely revealed.” It represents the final reality or the fully actualized state of the universe.

• Thirdness: Every measurable point on the line, representing any state or event in the universe, is a third. Thirdness is inherently relative because it exists between the first and the second, connecting them through time and process.

Peirce then describes different philosophical perspectives based on how one views the relationship between these two absolute points:

1. Epicurean View: If you think that the only reality is the measurable (the thirdness) and deny any ultimate beginning or end, then the “absolute” points are imaginary. This perspective sees no definite direction or purpose in the universe.

2. Pessimist View: If you believe that the universe returns to where it started, making the beginning and end the same (coincident), you hold a cyclical view of reality. This is pessimistic because it implies no true progress—just a return to nothingness or Nirvana.

3. Evolutionist View: If you believe that the universe is progressing towards a state different from where it began, you see the “absolute” points as distinct and real. This perspective views the universe as evolving towards something new and different in the distant future.

Peirce adds a footnote stating that “the last view [the evolutionary] is essentially that of Christian theology” (p. 251). Peirce’s statement reminds me of Owen Barfield’s comment in Saving the Appearances. “I believe,” writes Barfield,

“that the blind-spot which posterity will find most startling in the last hundred years or so of Western civilization, is, that it had, on the one hand, a religion which differed from all others in its acceptance of time, and of a particular point in time, as a cardinal element in its faith; that it had, on the other hand, a picture in its mind of the history of the earth and man as an evolutionary process; and that it neither saw nor supposed any connection whatever between the two” (p. 167).

Check out my essay on Barfield and Pierre Teilhard de Chardin for a deeper look at these connections.

The Triad in Psychology

Peirce considers “the Kantian form of inference” that would source the origin of his triadic logic in the shape of our own cognition; that is, he asks to what extent the triad may be “due to congenital tendencies of the mind” (p. 257-8). It may be that Peirce’s refashioning of Kant’s transcendental project constitutes an improvement, bringing the idea of the a priori more in line with his own evolutionary epistemology (eg, a historicization or biologization of Kant wherein what is a transcendental condition for the individual organism is an empirical contingency at the species level). But Peirce does not explicitly note his reinterpretation, making me wonder if it is a misinterpretation of the great Sage of Königsberg. Transcendental philosophy aims (even if it does not succeed) to lay bare the universal and necessary conditions of all experience, conditions that our knowledge of the facts of biology and psychology alike presuppose.

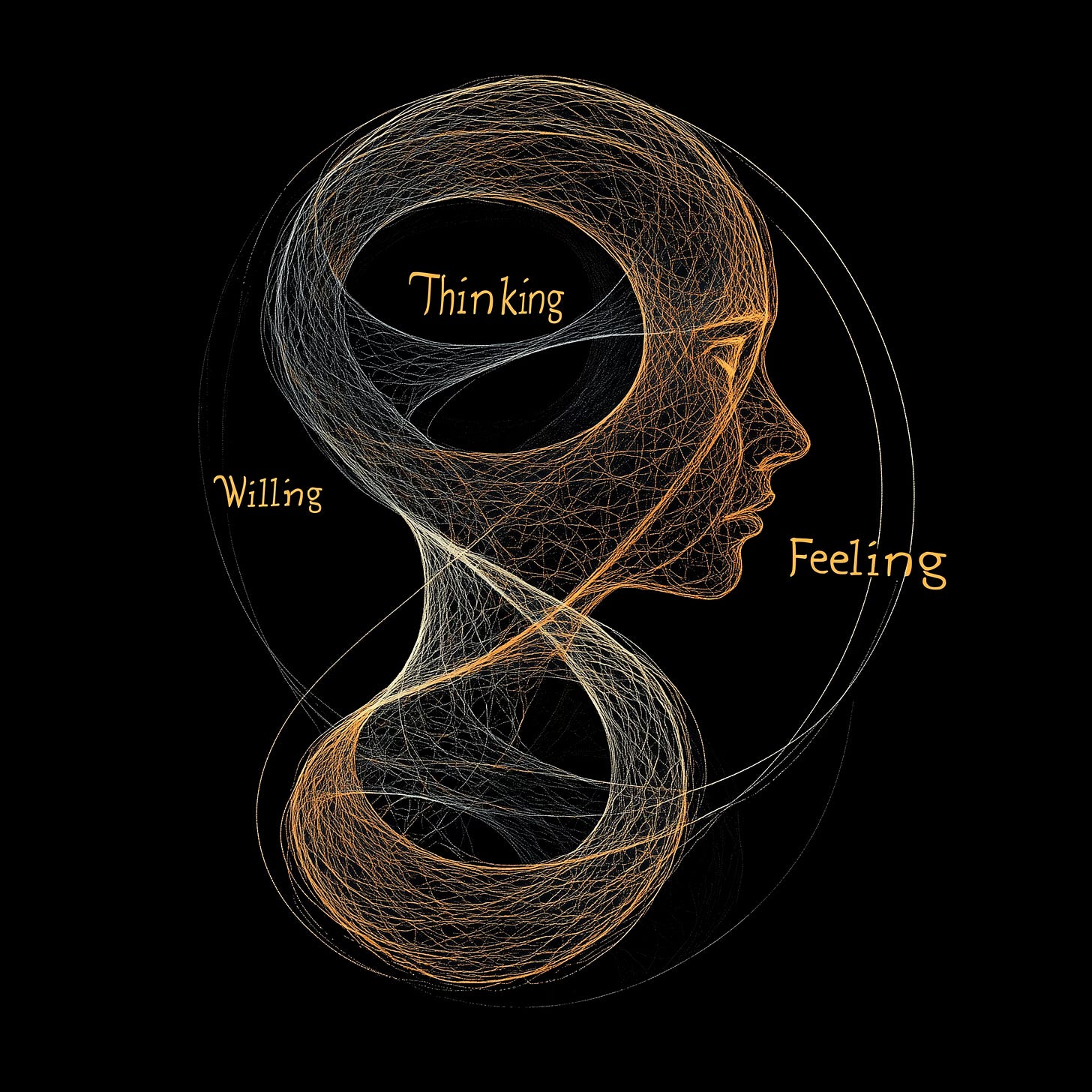

Leaving this issue to the side, Peirce goes on to consider the staying power of a rather ancient account of the tripartite structure of the human soul into thinking, feeling, and willing.

Peirce begins with the Firstness of feeling, distinguishing his view from that of Kant and most psychologists. While Kant and others often reduce feeling to sensations of pleasure and pain, Peirce expands the concept to include all immediate experiences. He views pleasure and pain as secondary phenomena, arising from “feelings produced by feelings” when through contrasts (to use a Whiteheadian concept) they reach a certain intensity. Peirce argues that feelings are the totality of what we are immediately and instantaneously conscious of—they are what is present to us in the moment. Their immediacy is fleeting, as we cannot be directly conscious of what has passed or what is yet to come. The instant we experience a feeling, it is gone, and we can never recover it as it was. Memory only falsifies it by imitation, as “nothing can resemble an immediate feeling” (p. 259).

Peirce next critiques the reduction of the Secondness of willing to mere desire. He objects to the idea, held by some psychologists, that the will is simply the strongest desire, by pointing to the difference between the wish-fulfillment of dreams and the actual activity of daily life. For Peirce, willing is not just about wanting something; it involves a distinct experience of action and reaction. The experience of punching or being punched is marked by a strong sense of objective reality and a clear distinction between the subject and the external world. He describes this experience as involving a “sense of polarity,” where there is a sharp contrast or opposition within the moment of willing—like a sudden shift from darkness to light requiring more than an instantaneous feeling to make sense of. If feeling is a consciousness of immediacy, willing is a consciousness of polarity.

Finally, Peirce addresses the complex Thirdness of thinking. Thinking is complex in the sense that it includes the other two modes of consciousness. Feelings are the basic elements composing cognition. Even pleasure and pain, though not ideal as standalone categories, contribute to our cognitive processes. The will, in the form of attention, also plays a crucial role, guiding what we focus and reflect on. In addition to attention, Peirce emphasizes the importance of objectivity, which he sees as even more critical to cognition than will. This sense of objective reality consistently redirects our attention and resists our will (whose difference from desire is here all the more apparent). What sets cognition apart from immediate feelings and the sense of polarity is the consciousness of a process: that of learning, acquiring knowledge, or mental growth. Unlike immediate consciousness (which is tied to a specific moment) or polar consciousness (which involves the sense of an occurrence with two sides), the consciousness involved in cognition cannot be contracted into an instant because it is inherently processual. It provides the temporal synthesis that binds the variety of life together. If willing is the pressing of a piano key, and feeling is the prolonged note this pressing produces, thinking indicates the melody that unfolds as further keys are played.

Peirce argues that the highest form of thinking is a kind of intellectual intuition that introduces a creative idea not contained in the original data but that reveals real connections that would not otherwise have been discovered. He feels this form of thinking “has not been sufficiently studied” and claims it shows the hidden affinity between poetry and science (p. 262).

“Intuition is the regarding of the abstract in a concrete form, by the realistic hypostatisation of relations; that is the one sole method of valuable thought. Very shallow is the prevalent notion that this is something to be avoided. You might as well say at once that reasoning is to be avoided because it has led to so much error; quite in the same philistine line of thought would that be and so well in accord with the spirit of nominalism that I wonder some one does not put it forward. The true precept is not to abstain from hypostatisation, but to do it intelligently” (p. 262).

The Triad in Physiology

While Peirce rejects materialistic (pseudo-)explanations of consciousness, he nonetheless expects to find some correspondence to his threefold logic in the structure and function of the nervous system.

How are the Firstness of feeling, the Secondness of willing, and the Thirdness of thinking evident in the neural ecosystem we refer to as our brain and senses?

Peirce explains that feeling arises from the active state of neurons. He notes that when nerves are cut, and communication with the rest of the community is severed, conscious feeling ceases, indicating that consciousness is closely tied to the networking of nerve cells (Forgive the gruesome image, but I believe his point is that if your big toe was yanked off and tossed into a fire, you’d surely feel pain in your foot, but you would not feel the burning toe. Still, it seems to me that phantom limb phenomena suggest we proceed with caution here). Peirce connects willing, which is the polar awareness of an action and its immediate effects (such as the sense of effort when moving muscles), to the discharge of nervous energy through nerve fibers. Thinking, he admits, is a much more complex knot to untangle.

He begins by trying to discover some neurological analogy for the cognitive procedure allowing us to find the resemblance between two or more sensations. In what way might the electro-chemical discharges of neural networks mirror the logical activity by which a conscious mind arrives at a judgment of identity? This suggests to Peirce that “two nerve-cells must probably discharge themselves into one common nerve-cell” (p. 263). But beyond just the power of nervous discharge, Peirce points to the power of taking habits:

“The genuine synthetic consciousness, or the sense of the process of learning, which is the preeminent ingredient and quintessence of reason, has its physiological basis quite evidently in the most characteristic property of the nervous system, the power of taking habits” (p. 264).

Peirce outlines five principles that explain how habits develop in the brain:

1. Spread and Intensification of Excitation: When a stimulus is applied to a nerve cell for an extended period, the excitation spreads to associated cells, increasing in intensity as it does so.

2. Fatigue and Path Shifting: Over time, nerve cells experience fatigue. This fatigue can cause the nerve cell to stop discharging along the usual pathway and either start discharging along a new path or increase discharge along a less used path.

3. Subsidance of Excitation: When the stimulus is removed, the excitation quickly diminishes, though it does not disappear instantly. A small remnant of the sensation can persist for some time.

4. Tendency to Repeat Previous Pathways: If a nerve cell is stimulated again after having discharged along a certain path before, it is more likely to discharge along the same path. This tendency to repeat previous actions is central to the formation of habits. But unlike with mechanical laws, which require lockstep obedience and rigid repetition of the same, the habit-taking tendency is subject to chance.

5. Forgetfulness or Negative Habit: If a nerve doesn’t react in a particular way for a long time, it becomes less likely to do so in the future, leading to a form of forgetfulness.

Given these physiological principles, a learning process is enabled to unfold. Peirce explains that when a nerve is stimulated, if the initial reflex does not resolve the irritation, the nerve will continue to adjust its response until the irritation is removed. When the nerve is stimulated again in the same way, it is likely to repeat some of the movements from the first time, especially the one that successfully removed the irritation. With each repetition, the brain strengthens the habit of performing the effective action, while less successful responses gradually fade. Over time, this process leads to the establishment of a habit where the correct response to the irritation is immediately triggered, as this response is continually reinforced, while other responses are weakened. Peirce illustrates this process of habit selection with an ingenious experimental analogy using a deck of playing cards that I’ll leave you read for yourself (p. 265ff).

Lest we start to imagine that Peirce is reducing Reason to the wrinkles of our nervous tissue, he reminds us of the mysteries of the intracellular protoplasm. Attempts to explain the living activities underway within cells by reference solely to chemical reaction chains would be to explain the unknown by the even more unknown. Instead of seeking a chemical or physical explanation, Peirce returns to his logical triad. The various “properties of protoplasm” are distilled to three: sensibility (Firstness), motion (Secondness), and growth (Thirdness).

Peirce reasons abductively that our human kind of consciousness is an emergent “public spirit among the nerve-cells” (p. 246). But delve a layer deeper into the brain to consider a single neuron. Though in profound synchrony with the cellular community each one is also already a sentient agent in its own right. Now dive beneath the cell membrane and enter the living molecular matrix within. Even the proteins composing each cell are protean processes and not machine gears, better described in terms of their “elastico-viscous…slow streaming motions” (p. 267). Even the molecules of which we are made are habit-taking learning-agents (Thirds).

The Triad in Evolutionary Cosmology

Akin to Whitehead’s “cell-theory of actuality” (Process and Reality, p. 219), Peirce is led to interpret the entire world-process as a complexifying community of habit-forming feelings. He thus pursues “a natural history of the laws of nature” (p. 246) where the interplay of chance and habit drives a pan-sensual process of cosmic learning and evolution from quarks and quasars to koalas and Kashmiri Acharya. From the first proton to the Adam Kadmon, the cosmic continuum feels, resists, and responds. Everything actual is expressive of this triad.

The cosmos is an evolving process where spontaneity (Firstness) gives rise to actual events (Secondness), whose chanciness is then organized into habits or laws (Thirdness). Peirce argues that the presence of chance in the universe means that the so-called “laws” of nature are only approximations, not absolute truths. This view challenges the traditional onto-epistemics of certainty, which had been foundational for at least the Cartesian approach to modern science. Peirce goes so far as suggesting that even the principles of physics are rooted in original, instinctive beliefs that are later refined through experimentation. All inductive inference from experience, he reminds us, depends on statistical sampling and so can only yield approximate truths. This is not just because of the practical limits of our observations and measurements, but because nature itself is pregnant with possibilities: spontaneity is as real as it gets.

Peirce contends that law emerges out of pure chance, generating an evolutionary process of selection in which lawless originality mingles with lawful conformity. For Peirce, nature is not only self-generative, it exhibits a tendency towards generalization, whereby the probability of events repeating under similar conditions increases over time. This concept of nature as self-generative and self-generalizing leads to his view that time and space themselves are emergent phenomena.

Peirce sees the original chaos (Firstness) as timeless, with ordered time itself an emergent regularity. He also suggests that there are multiple, potentially discontinuous time streams (p. 278), and that space arises (via Secondness), as states undergo changes. Habit-formed bodies, by their movement from place to place, render space more like themselves, and thus more uniform. There are strong parallels here with Whitehead’s so-called “epochal theory of time” and account of the emergence of space-time via the mutual prehensions of actual occasions of experience, which themselves do not occur within an already constituted physical space or time (PR, p. 283). There is thus, for Whitehead (as, it would seem, for Peirce—despite his synechism) a becoming of continuity, but not a continuity of becoming (PR, p. 35).

Implications for Metaphysics and Science

Peirce’s views have significant implications for metaphysics, logic, and natural science. He notes the “unconditional surrender…by mathematicians of [his] time of the absolute exactitude of the axioms of geometry” (p. 273). While geometry was always a trickier case, Bertrand Russell and Whitehead would make one last go at the formalization of arithmetic a decade and a half later. Their project became entangled in a nest of paradoxes, frustrating Russell but liberating Whitehead to pursue a new kind of speculative philosophizing (a story I tell in more depth here). Peirce, like Whitehead, accepted that philosophical reasoning should give up the attempt to ape mathematics by dressing itself up in the style of geometrical proof. A pragmatic approach to metaphysics becomes unavoidable given the probabilistic, evolutionary nature of our universe.

A tentative parallel with Whitehead’s process philosophy occur to me in regard to Peirce’s treatment of real and rational relations, which at first blush appear akin to physical and conceptual prehensions, respectively.

Notably, like Rudolf Steiner in his “Light Course,” Peirce makes clear that the parallelogram of forces divides something real (velocity) into the sum of two other measures (distance and time) that are not real but “mere creations of the mind” (p. 255).

Hopefully some applications to evolutionary love 💕🌌

Very good Matt, I'm really trying to deepen my understanding of Pierce and Whitehead. In many ways it's clear to me that much of our modern work hasn't quite caught up yet