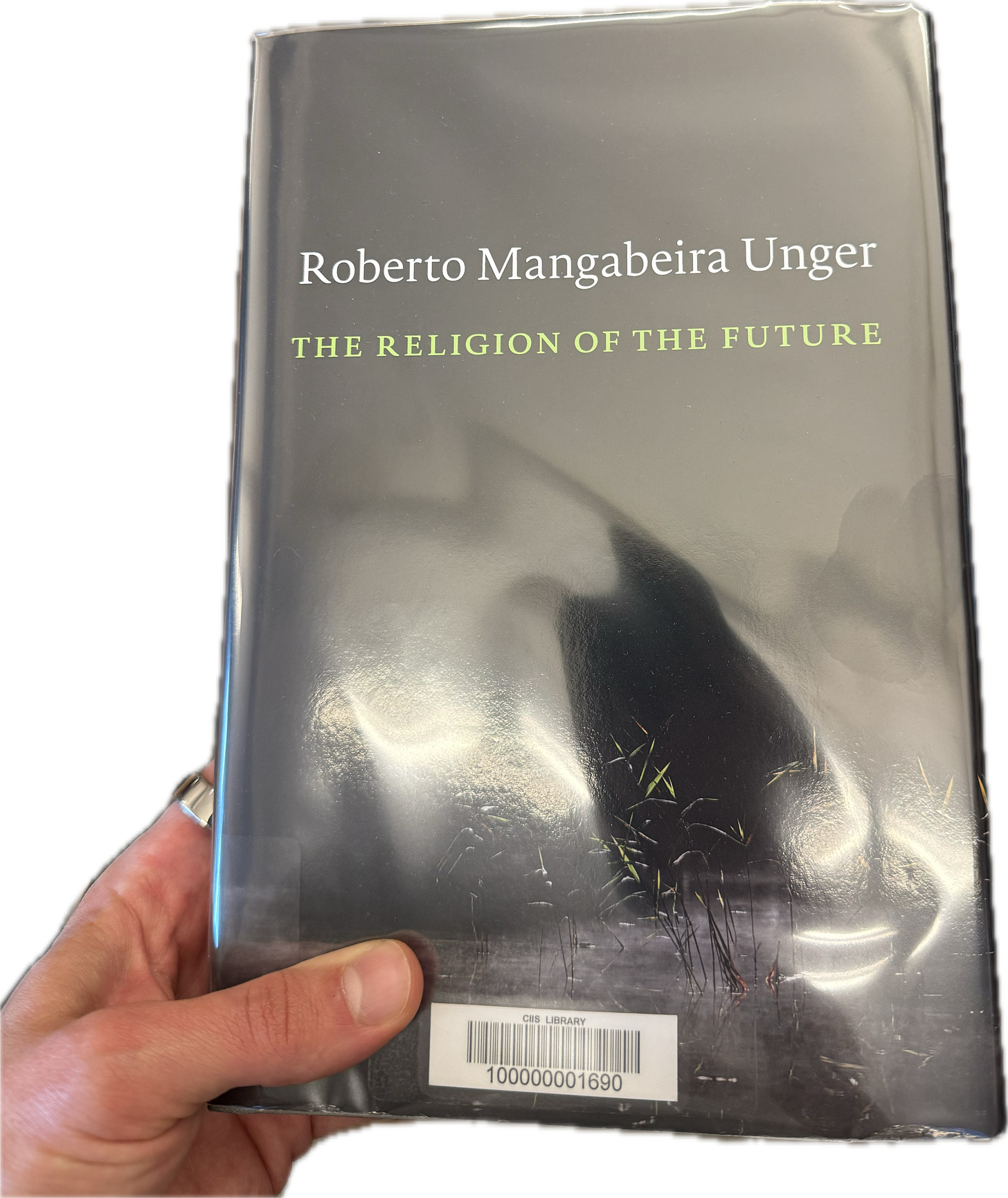

I picked up Roberto Unger’s book The Religion of the Future (2014) for the first time yesterday.

On the back cover of his book, this excerpt is printed:

Everything in our existence points beyond itself. We must nevertheless die. We cannot grasp the ground of being. Our desires are insatiable. Our lives fail adequately to express our natures...

If the vocation of man is to be godlike, man as he has been is, as Emerson wrote, a God in ruins. To the never healing wounds of mortality, groundlessness, and insatiability, the indifference of nature, the cruelty of society, and the corruption of the will add the burdens of belittlement-both imposed and self-inflicted

We squander the good of life by surrendering to a diminished way of being in the world. We settle for routine and compromise. We stagger, half-conscious, through the world. Anxious for the future, we lose life in the only time that we have, the present. This squandering is a dying many times. Our interest is to stop this dying, so that we can live until we die all at once.

I’ve barely cracked the book, but I’ve spent some time with Unger’s lecture on the same subject:

“There are three possible points of departure for a religious Revolution. The first is the continuing conflict between the promises of the struggle with the world and our established beliefs, ways of life, and social arrangements. The second is our willingness to recognize the ineradicable flaws in human life for what they are: our mortality, our groundlessness, and our insatiability (and our susceptibility to belittlement). The third has to do with this fourth defect, belittlement, because the set of beliefs that exercises the greatest authority around the world promises humanity elevation to a higher life—a share in the attributes of the divine.”

Unger calls us to face the basic facts of our increasingly lonely co-existence as denizens of an imperiled planet. Rather than allowing us to retreat into existential angst, this confrontation can spur us into what he calls a “religious Revolution.” There is both a sacred and a secular form such a revolution might take. The sacred mode locates our spiritual ascent within the larger narrative of our relationship to God, while the secular or “purely profane” mode remains confined to a story of common descent and cumulative transformation. Either way, Unger calls for a transformation of existing ideas of self and society that have come to define our “belittlement,” our acceptance of half-lives, and our frequent failure to realize our own godlike creativity.

I cannot help but feel a deep resonance with Rudolf Steiner’s account of the “consciousness soul” age, what we normally call the modern period beginning around 1500 and accelerating Western and now planetary civilization into its current techno-scientific and capitalist religion of individualism. We all feel it today, the climax of this anti-cosmology, the overwhelming tide of nihilism that in the late 19th century only a few began to feel. Today everyone is drowning in it. The human being stands before a vast nothingness outside themselves, and a dizzying groundlessness within themselves. Unger refers to our confrontation with nihilism as “the fear that our lives and the world itself may be meaningless.” Steiner recognized that our inherited religions, once intimately connected to cosmic realities, no longer speak to modern individuals as they once did. Simultaneously, a purely materialistic worldview like scientific naturalism inevitably reduces human striving to mechanical processes, leaving little room for genuine moral freedom. Unger diagnoses this crisis in modernity as a spiritual predicament that demands a revolutionary response. Steiner, too, saw the urgent need for psycho-social renewal that would address both the illusions of easy transcendence and the dead-end of flat immanence.

I wanted to share some reflections on how Unger’s religious revolution intersects with Steiner’s perspective on human freedom, cosmic evolution, and the task of our time to become conscious co-creators of divine nature. Both thinkers call for a radical shift: rather than comforting ourselves with illusions and deferrals, we must willingly face our own and others ineradicable flaws as the necessary crucible for discovering a deeper spiritual freedom and rekindling community life and networks of trust. While I don’t know Unger’s theological views very well yet, my preliminary sense is that he affirms there is more to reality than the measurable stuff of the physical world. As in Steiner and the wider wisdom streams he represents, the human being is affirmed as a living bridge between the earthly and the divine—destined to bring forth new life in the very midst of groundlessness.

Unger’s Three Points of Departure and the Consciousness Soul Crisis

Unger begins his lecture above by identifying three possible points of departure for a religious revolution:

The conflict between the struggle with the world and established arrangements: By “struggle with the world,” Unger means the central spiritual orientation rooted in the Semitic religions of salvation (Judaism, Christianity, Islam) and in modern secular projects of liberation (democracy, liberalism, socialism). These traditions promise that human beings can participate in a larger cosmic or historical drama leading to salvation or emancipation. But this promise stands in tension with the ways we actually live, as well as with many of our entrenched beliefs and institutions.

Our willingness to recognize the ineradicable flaws of human life: Unger catalogs these as mortality, groundlessness, insatiability, and our susceptibility to belittlement. Traditional religion often tried to deny these flaws or explain them away, offering us cosmic narratives that soothed our anxieties. But we can only renew our collective spiritual life when we renounce this denial. We must hold fast the facts of our earthly lives and transform them from curses into precious gifts.

Our susceptibility to belittlement: Belittlement is the lived contradiction between the godlike promise of the world religions and secular ideals—“every ordinary man and woman is Godlike”—and the daily squandering of life in routine, compromise, sleepwalking, and half-consciousness.

Steiner’s account of the “consciousness soul” runs in parallel with Unger’s sense of our place of departure. Steiner describes modern humanity as alienated from cosmic meaning, having built for ourselves a mechanistic picture of the universe in which it appears earth is just a typical dust particle planet flung through the vastness of empty space, that we are one animal species among others, all products of the blind and bloody machinations of biological evolution. Many contemporary people are awash in groundless anxiety, fearful of the nothingness at the core of our being and at the heart of the cosmos. Steiner and Unger agree that this confrontation with nothingness is not a mere misfortune. It is the seedbed of new forms of transcendence and spiritual transformation. For both, the danger is that we may settle for trivial or compromised ways of living, squandering the auspicious occasion of our present incarnation. The promise, however, is that by squarely facing groundlessness with love in our hearts, we may find that a new creative freedom, radiant and warm, springs into action within and between us.

Unger’s Four Components of Religious Revolution and the Awakening of Etheric Life

Unger outlines four main components for this program: the overthrow, the self-transformation, the transformation of society, and the reward. Each responds to one dimension of our predicament and aims to guide us from groundlessness toward the spiritual uplift of life.

The Overthrow

Unger identifies the greatest spiritual danger for modern humans as the squandering of life in compromise, routine, and sleepwalking. We die “many small deaths” by never living fully. We must overthrow ourselves—both the thought-forms in our own psyche that keep us small and the social conditions that enforce our belittlement. This overthrow is energized by our confrontation with the ineradicable flaws of human life:

“Our mortality, our groundlessness, our insatiability... by holding them squarely before us and by resisting the temptation to deny them, we steel ourselves against the inclination to compromise and to belittlement.”

Steiner, in a similar vein, emphasized that the first step to genuine self-awakening is to face the fact that the physical universe described in great detail by scientific materialism does not leave any room whatsoever for human souls or spiritual beings. In our modern knowledge of nature (including human nature) as a machine, we confront an abyss within and without. We feel the contradiction in our sense of pride in having mastered nature and the loneliness and alienation such mastery inevitably produces (not to mention the rude awakening of the ecological and climatic catastrophe to remind us that our pride in mastery was premature). The struggle with this contradiction triggers our capacity for free thinking and moral intuition. The “overthrow” Unger describes is echoed in Steiner’s counsel that we cannot rely on old authorities or inherited dogmas to pull us out of our half-conscious haze; we must will ourselves awake.

Unger goes on to say that no single confrontation with mortality, groundlessness, or insatiability suffices on its own. This confrontation must be supplemented by social and cultural practices that remind us of the “artifactual character” of all our social arrangements. Society and our political processes should be organized to reveal that all frameworks are provisional, so that as a matter of our ordinary democratic life together we are led to question and regularly revise our collective agreements. Thus, “institutional and ideological idolatry” is avoided. However, until such a reconstruction of society occurs, Unger reminds us each that an individual can still create a surrogate for that structural fluidity by transforming our relationship to our own character. Far from allowing the self to calcify, we should break the self’s “mummy-like rigidities” from within, refusing to let habit and routine define us. In Steiner’s language, we must gain a new consciousness of the etheric life that used to animate the world religions.

Self-Transformation

Unger envisions this second part of the revolution as a reorientation of our attitude to one another and to existence. He formulates it as either a doctrine of the virtues or an account of the mind’s spiritual (anti-mechanistic/non-computational) capacity. The virtues, in his articulation, include:

- Pagan virtues of connection: fairness, forbearance, respect, and courage. These guard against our tendency to see ourselves as the center of the world.

- Virtues of kenosis (emptying out): simplicity, attentiveness, and enthusiasm. These help us avoid mistaking the peripheral for the central and remain open to the truly vital.

- Virtues of divinization: openness to the new and to other persons. These cultivate the recognition that we are “death-bound but transcendent spirits,” uncontained by any closed context.

Alternatively, he describes the mind as more than a machine—an “anti-machine” capable of negative capability (Keats), recursive infinity, and transgressing its own limits:

“The higher life to which we aspire is the life of the imagination… [we prize] the anti-machine over the machine... so that we come to live life as surprise.”

Steiner, especially in his Philosophy of Freedom (1894), likewise argued that real moral freedom arises when we transform our thinking into a living, creative activity. By consciously developing our will to shape our own concepts, we discover that each human being is a “transcendent spirit” in precisely Unger’s sense. True freedom can only flourish if the self is not allowed to mummify into a fixed generic identity. Instead, we are tasked with continually re-creating ourselves in light of moral intuitions we generate out of the etheric life within us.

Transformation of Society

The third component of Unger’s religious revolution addresses how society is organized. Even the freest, most egalitarian contemporary societies fail to serve as adequate homes for beings like us who aspire to a higher life. In his words, “life is what we have, but life is also what we squander,” because the social system confers opportunities unevenly, organizes work in repetitive ways better suited to robots, and discourages political creativity until crisis strikes.

Unger highlights four major deficiencies in current societies:

- Hierarchical segmentation of the market economy: we need legal and institutional innovations that democratize the market, turning it into “a permanent experiment in the forms of practical cooperation.”

- Anemic representative politics: “No trauma, no transformation.” Unger calls for “high-energy democracies” that raise the level of organized popular engagement and expedite structural experiments.

- Weak bases of social solidarity: these are typically restricted to the boundaries of money transfers (redistributive programs). True solidarity, he argues, should be built on direct responsibilities “to take care of other people outside one’s own family.”

- Inadequate education: the school must be “the voice of the future,” recognizing “the tongue-tied prophet” in every child. Beyond being merely analytical, education should be dialectical, teaching every subject from at least two contrasting points of view to free the mind from superstition.

In this way, we move toward what Unger calls “a structure of no structure,” a social order that “invites its own revision” and hence continuously dissolves the illusions of necessity. As the anthroposophical social reformer and artist Joseph Beuys would say, we must let go of social structure to begin social sculpture, where life itself becomes a collaborative art project. Steiner created a new approach to education that encourages and cultivates freedom of thought and expression. In his Waldorf pedagogy, the child is recognized as a soul-spiritual being with a pre-earthly existence, and education is an art that fosters each child’s unique way of expressively inhabiting their earthly lives.

Steiner saw the modern period as a time requiring us to become “self-legislating,” freeing ourselves from blindly imbibing external cultural forms and the scramble of social Darwinism to instead build an associative, cooperative social order. Unger’s institutional proposals, while not couched in terms of Steiner’s “social threefolding” proposal, resonate profoundly with the latter’s attempt to imagine and enact new social forms that do not degrade or belittle our innate godlike potentials.

The Reward

Finally, Unger describes the reward for these efforts as “life itself, lived while we have it.” It is not necessarily eternal life, but a quality of existence in which we engage the social world wholeheartedly without surrendering our individuality. We connect intimately with others, open ourselves to love, and defy the old categories that once served as the boundaries of our identity:

“We shall soon die... although we feel that we should not. We shall die without having understood what this strange world is really about. Our religion should begin in the recognition of these terrifying facts rather than in their denial. It should arouse us and teach us to change our societies and ourselves.”

For Steiner, this echoes the moral intuition that the highest spiritual achievement is to live in freedom and love until our final breath in these earthly bodies. Our “reward” is not a static heaven but the continuous unfolding of divine creativity in and through our humanity. Unger’s “we become all of us, not just a happy few, bigger as well as more equal,” finds an analogue in Steiner’s view of humanity as collectively engaged in forging the future of cosmic evolution as a bridge between heaven and earth.

Steiner’s Spiritual Hierarchies and Their Participation in Human Evolution

Whereas Unger’s program focuses on political and existential transformations, Steiner extends the narrative into a cosmic drama. He speaks of ancient cosmic epochs—Saturn, Sun, and Moon phases, in which the spiritual hierarchies shaped successive layers of our human constitution (physical, etheric, astral).

On Earth, the human “I” incarnated, enabling our self-conscious freedom. Central to Steiner’s cosmology is the Mystery of Golgotha, in which the Christ Being entered earthly evolution from beyond the highest ranks of the hierarchies.

Yet Steiner’s emphasis on the new impetus in modern times—in which materialism has overshadowed older spiritual insights—dovetails with Unger’s claim that we cannot rely on past religious forms that denied or downplayed human flaws. Steiner observes that our era, the consciousness soul age, demands we face the apparent “nothingness” within ourselves and behind the world. Only once we’ve accepted our fallenness can we recognize and then accept the help that is offered by the Christ Being.

Unger himself warns against “the halfway house of partial belief,” seeing it as “an instrument of self-deception.” Either we fully commit to an idea of a personal God who intervenes in history (and thus “double the bet”), or we remain in a secular narrative that radicalizes the message of the struggle with an intransigent world with purely human resources.

Groundlessness, Freedom, and the New Etheric Consciousness

A central theme for both Unger and Steiner is the role that nothingness, or groundlessness, plays in human development. Unger boldly asks us to face our mortality, our existential insecurity, and our insatiable nature—not to fixate on them as final limitations, but to be ontologically shocked into an overthrow of our usual half-alive state. Similarly, Steiner writes extensively about how the consciousness soul age compels us to look into the abyss where the old gods once stood. The sense-bound intellect presents us with a hollow material universe; traditional beliefs no longer convincingly mediate the divine. But the “nothingness” we find inside ourselves is precisely the opening where a renewal of creative life may be found. With a bit of faithful watering, what appeared as barren soil begins to sprout. The soul is baptized and born again in the spirit.

Steiner’s Philosophy of Freedom is an early articulation of this metanoia. Our moral intuitions do not come from external commandments or rational duties but from an inward fountain of creativity through which each individual shapes concepts and moral ideals out of their own thinking activity. Unger’s description of the mind as an “anti-machine”—capable of indefinite recombination and negative capability—is similarly suggestive. This capacity to generate novelty, to “live life as surprise,” is the kernel of what Steiner calls the exceptional state of spiritual activity in our thinking.

Overthrowing and Reorganizing Society: The Bridge Between Earth and Heaven

Unger underscores that his religious revolution is not merely internal. It also demands transformation in social arrangements—our schools, our politics, our economies. Steiner frames the same imperative in terms of bridging spirit and matter: we must create social forms that do not degrade or imprison our spiritual potentials. Both speak of an educational reform that recognizes each individual’s capacity for self-transformation. Both highlight the need to reorganize economic life so that it becomes a site of collaborative experimentation rather than a system of hierarchical segmentation.

In the face of human belittlement, Unger and Steiner both make clear that a purely intellectual critique of materialism will not suffice. Unger demands the enactment of new institutional designs; Steiner advocates living spiritual practice and a recasting of the arts, sciences, and community life. They both see that real transformation must extend beyond theoretical criticisms into the tangible ways we live, work, play and imagine.

Unger calls for a new theology of redemption in which God’s indwelling is manifest in a series of moral and political transformations. This would require a radical renovation of the theology of incarnation so that salvation, though it extends beyond history, must begin in our present existence here and now. The “divine must live within the world.” We must resist otherworldly abandonment of society.

Steiner’s view of Christ’s incarnation and the continuing influence of spiritual hierarchies in human evolution supplies a cosmic narrative for those who would take Unger’s “sacred track.” The Event of Golgotha is understood as a divine sacrifice that seeded the Earth with the transformative power of divine love. Our challenge is to actualize that power in free human hearts through a moral and social revolution.

On the “profane or secular track,” one might bypass explicit references to a personal God and angelic hierarchies and focus instead on a story of cumulative transformation, culminating in the same aim: the enrichment of life. Unger’s message is that we can become bigger, more alive, more equal, connecting with one another in love without paying the price of subjugation. In Steiner’s terms, one could interpret this path as discovering the spiritual in the creative forces of thinking and cultural life without naming those forces “divine.” Steiner himself, in Philosophy of Freedom, did not yet speak of angelic hierarchies aiding human evolution. He pointed instead to the human capacity for free thinking and moral intuition. It is plausible that the younger Steiner was traveling on a profane track parallel to Unger’s call for imaginative self-transformation—though Steiner eventually reintegrates his profound insights into human freedom back into a sacred cosmic narrative.

Unger notes the risks of both tracks. A sacred track always “doubles the bet” by committing to a divine personal being for which we have no conclusive proof, thus exacerbating “the disparity between the weightiness of spiritual commitment and the inadequacy of the grounds for making it.” The purely secular track can fall into a “new paganism” that might simply romanticize the ineradicable flaws of human life. Steiner’s solution is to cultivate direct spiritual perception—an etheric imagination—so that the cosmos discloses its living heart. This resonates with Unger’s refusal to reduce the mind to a machine, yet it also underscores that no conceptual argument alone can fully close the gap between human belief and divine reality. Recognizing the living Christ already pulsing in our heart requires an experiential encounter and is not the result of a logical proof.

A Shared Vision of Human Ascent

In Unger’s lecture, we hear the call to “stop dying many times” by refusing to settle for a diminished life. He insists we engage the “overthrow” of our own petty routines, practice self-transformation, reorganize society, and realize our reward in the fullness of life here and now. We can carry out this project either in a sacred or in a secular key, but we cannot linger in a muddled halfway. Unger’s insistence resonates strongly with Steiner’s conviction that the consciousness soul age must discover a new mode of transcendence. The old religious forms offer what has become for us a too easy transcendence, as escape for the weak and worthless to those who have glimpsed the immensity of the cosmos and who dimly feel the wellspring of freedom roiling within themselves.

For Steiner, the new religious or spiritual consciousness emerges from the recognition that creation is an ongoing, cooperative activity, with human beings as a bridge between earthly and heavenly worlds. Unger would say the same, albeit in different terms: we are “embodied, death-bound, transcendent spirits,” uncontained by context, compelled to expand our share in the attributes of divinity—whether we name it “divine” or not.

Steiner’s esoteric cosmology and Unger’s existential-political proposals converge on this point: human beings must confront the groundlessness that once seemed terrifying, and kindle within it a living imaginative thinking that inspires transformative action. Out of this creative fire, a new impulse for selfhood, community, and cosmic belonging can be born. If we step across the threshold with courage, “we shall live until we die all at once,” partaking in the ever-transforming flame of vitality rather than succumbing to the little death of yet another wasted day.

Hi Matt,

I don't get the sense that Unger in any way means by "spirit" and "nothingness/groundlessness," e.g., in the same sense that Steiner or other spiritually oriented philosophers mean it, or that he draws any of his philosophy from spiritual sources. He has been involved in politics for 50 years, not meaning to downgrade that, since he seems to be doing it from a good place, but just to say that he is very out there in the world, and this book specifically seems to be another expression of his sincere efforts to bring the world forward.

Furthermore, his philosophy is clearly materialistic. It is said that he "takes on the Newtonian idea of the independent observer standing outside of time and space, addresses the skepticism of David Hume, rejects the position of Kant, and attacks speculations about parallel universes of contemporary cosmology." From what I've read, he seems to be offering a post-Richard Dawkins style religion, something that Dan Dennett would have agreed with. Yes, one could paraphrase what he's saying as, "One should live to the utmost in the moment but in the context of history," but Unger would not mean that the way Buddha or even Whitehead would mean it.

What I'm trying to say is that to me at least it sounds dissonant and jarring to place a spiritual teaching next to a material philosophical one for comparison unless you're implying that he picked up on Steiner's ideas in ways unbeknownst to him or is himself a closeted anthroposophist, or is simply expressing a materialist's view that just happens to be, again, unbeknownst to him, a practical application of some of Steiner's ideas.

Great connections, Matt. My sense is that Steiner's approach can help resolve Unger's recognition of the "disparity between the weightiness of spiritual commitment and the inadequacy of the grounds for making it.” Doing so would also illuminate Unger's ideas in a new light, particularly his notions of sharing "in the attributes of the divine"—becoming "bigger, more alive, more equal, connecting with one another in love": participated experience.