Below is a draft of my review of:

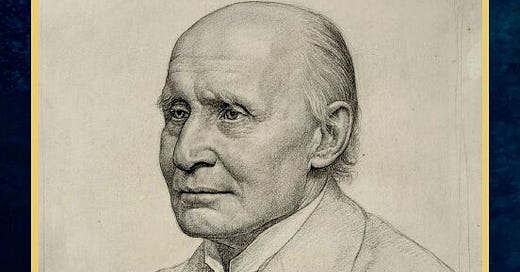

BRIAN G. HENNING, JOSEPH PETEK, and GEORGE LUCAS, eds. The Harvard Lectures of Alfred North Whitehead (1925-1927): General Metaphysical Problems of Science. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2021: lxii + 511 pages.

The version that is eventually published in Process Studies will likely need to be about half this length, so I’m sharing the whole thing for your reading pleasure below.

The second volume of The Harvard Lectures of Alfred North Whitehead, edited by Brian G. Henning, Joseph Petek, and George Lucas, provides a further glimpse into the evolution of Whitehead’s thought during his early Harvard years, 1925–1927. While it is probable that these volumes will remain a delicacy feasted on by only the most devoted Whitehead scholars, the Whitehead Research Project’s tireless efforts to publish a complete critical edition are well timed to meet a growing worldwide interest in the radical alternative to mechanistic reductionism found in his organic cosmology. Future interpretation of his published works will surely be aided by the existence of these carefully edited and painstakingly indexed student notes.

As Adam Scarfe noted in his review of HL1[1], these student notes do not grant us a pristine, unfiltered look into Whitehead’s imagination. Readers expecting faithful transcripts of Whitehead’s lectures will be disappointed, but this is an unrealistic expectation that does not detract from either volume, which successfully open a new window (if not a doorway) into Whitehead’s mind in action. What becomes apparent more than anything else is the way Whitehead conducted his philosophical education in public. His struggle in Emerson Hall to find an original relationship to the universe is evident in his students’ struggle to understand him. On the editors’ own admission, the notes available for the second volume were in considerably more disarray than those included in HL1, with many containing errors and omissions. Except for his remarks to Cabot’s Social Ethics class[2], what we have is not a literal transcription of Whitehead’s lectures but a creative reconstruction of the living philosophical co-inquiry that went on in his classroom. Despite not resolving all ambiguities, the sketches these student notes preserve shed significant light on how Whitehead grappled with pivotal questions during the still larval phase of his metaphysical project. He told his Harvard students early in his first semester that his task was to get the new science into a form that philosophers could understand.[3] But as became clear as his Harvard career unfolded, his broader project was also to help scientists themselves understand both the metaphysical presuppositions of their discipline as well as the cosmological implications of their own recent discoveries. Following the trail of Whitehead’s thinking through his students’ notes dramatizes important ideas that may otherwise have remained insufficiently contextualized by his published corpus. The remainder of this review examines a few examples of what additional context may be gleaned from the pages of HL2.

From the outset, Whitehead challenges the Baconian legacy that elevated empirical observation of brute facts while casting aside Aristotle’s principle of sufficient reason and final causation. This early modern revolt against scholastic metaphysics, though fruitful for the advance of natural science as an instrumental method, left a lingering philosophical difficulty: the problem of induction. How do we move from the observation of particular instances to the general or universal laws that scientists routinely claim to discover? Whitehead would eventually address this question in great depth in Process and Reality[4], but in the fall 1925 semester he hints that part of the answer lies in recognizing that thought is always an analytic act of abstractive selection. No bundle of concepts can ever fully exhaust the concrete particular it seeks to analyze, because every actual entity carries within itself a multiplicity of elements—some relevant to our purposes, others not. This insight underpins what Whitehead calls his “organic empiricism,” the notion that good theories are those whose ideas both cohere internally and sufficiently express the features of the experiential world that matter to us, while acknowledging there is always something more left unaccounted for. Whitehead’s debt to William James’ radically empirical method has been well established, but the novel and perhaps more apt phrase “organic empiricism” features only in HL2, never making it into his published works.[5]

Whitehead dwells on his divergence from Kant’s view that universality and necessity are a priori aspects of our mental organization that must be added to experience. His alternative view is that universal forms are inextricably entangled with actual occasions of experience. Echoing Aristotle’s claim that each immediate occasion is a union of being and non-being, Whitehead suggests that non-being corresponds to what he terms “beyondness,”[6] the fact that any single act of experience must include reference to realities beyond itself. Thus, instead of imagining universals as either transcendental categories structuring cognition (Kant) or transcendent ideas recollected in the soul (Plato), Whitehead treats them as real potentialities that function within concrete occasions throughout the cosmos. He calls this “organic empiricism” because each occasion’s unity is achieved by fusing the immediate data of its physical inheritance with conceptual possibilities (or “eternal objects”).

Whitehead’s keystone concept, “concrescence”—the process by which many diverse factors “grow together” into one emergent actuality—makes its first appearance in Conger’s notes on October 21, 1926.[7] In the same lecture, Whitehead also uses terminology not seen in HL1 to distinguish between a “physical pole,” where efficient causality and direct inheritance of the past predominate, and a “mental pole,” which introduces conceptual analyses and imaginative possibilities. This “dipolar” conception of concrete fact was explicitly introduced during his lectures in King’s Chapel, Boston, in February 1926, published later that year as Religion in the Making. Regardless of exactly when Whitehead arrived at his preferred terminology, the publication of his student’s notes reveal that the conceptual background of his mature scheme was in utero from the moment he first ascended a lectern at Harvard. In the lightest atomic element and the deepest reflections of a human mind, there is always some measure of inheritance and some creative advance toward a fresh pattern of value. In this sense, final causality—traditionally associated with purpose or teleology—becomes not an extraneous add-on to a world of efficient causes, but an intrinsic ingredient in all natural processes. Whitehead repeatedly stresses that the concept of function requires what he calls a “depth of time”: an organism or event must integrate not just what came before (efficient causation) but the lure of what might yet be (final causation).[8] One of the reasons he rejects a purely morphological or shape-bound account of nature (natura naturata) is that it neglects the ongoing activity by which concrescent occasions generate emergent values (natura naturans).[9]

Despite his relative praise of Plato’s influence in Process and Reality, HL2 also reveals Whitehead’s criticisms of Plato’s exaltation of static geometric forms. Rather than treating ideal forms as otherworldly perfections that overshadow the feeble attempts of passing facts to imitate them, Whitehead inverts the Platonic doctrine by re-envisioning the cosmos as a creative flux of occasions that partially realize eternal objects in an ever-evolving harmony. This emphasis on harmony and value in the flux resonates with Heraclitus, whose approach Whitehead admires and seeks to reconstruct.[10] Where classical empiricism tended to dismiss future possibilities as wholly unknown or arbitrary, Whitehead’s organic empiricism posits that each event must already include a definite (and distinct) relation to past and future occasions mediated by eternal objects, thus allowing for a participatory, non-deterministic relationship to the whole amplitude of time in each and every momentary occasion.

Whitehead’s organic empiricism could also be described as onto-epistemic, in that it challenges any system in which knowledge remains external to what is known. Throughout these lectures, he insists that a complete metaphysics must incorporate the act of cognition into the fabric of nature. If our account of reality renders knowledge impossible or isolates mind as a substance wholly cut off from the physical world, we have failed to give an adequate description of what is actually happening. By contrast, his doctrine of “prehension”[11] allows for a direct inclusion of other occasions—physically inherited and conceptually transformed—within each new occasion. This means that subject and object, knower and known, are not separately enduring substances but relational dipoles within a dynamic universe composed of countless intra-dependent occasions of experience. What is an object in one moment of experience enters into the subject of the next, only to again perish as a superject to be inherited by the next round of concrescence.

In his first year at Harvard, Whitehead’s students’ notes contain only the first inklings of his later process-relational innovations in theology. In HL1, he mostly complained about modern philosophers who called in God willy-nilly to solve metaphysical difficulties. Of course, in Science and the Modern World (1925) he had himself found reason to introduce God as a “principle of limitation” on possibility.[12] Bell records the following explanation in his notebook on March 7, 1925: “If your consciousness of God grows out of your Metaphysics that is all right. But easy assumption of fundamental being to solve all difficulties ‘straight’ is the bad thing.”[13] On the same day, Hocking records: “God is another individual, & no more reason why you should see ideas in the mind of God than in the minds of each other.”[14] Clearly the categorical obligations of Whitehead mature scheme were already constraining his speculations. God was not to be an exception to but the chief exemplification of the metaphysical categories. A year later, around the time of his delivery of the lectures that became Religion in the Making (1926), Whitehead is recorded as “waving friendly signals to [Kant]” in uncharacteristic agreement with the Königsbergian philosopher’s sense that the systematic unity of nature is unthinkable without the ideal of God.[15] And yet, rather than allow God to remain an exception to the categorical conditions applying to nature as we experience it, Whitehead is recorded as insisting that the same dipolar “physico-mental…principle applies to God as to an electron as…to ourselves.”[16] Where Descartes affirms that all minds and bodies require God’s concurrence in order to exist, Whitehead goes even further: “that proposition is not peculiar to God because,” if causality and knowledge are to be taken as real, then “all [things must] require each other in order to exist.”[17] Whitehead is then recorded as provocatively referring to “the catastrophe of German Idealism,” which he seems to have understood to have followed from this school’s acceptance of Descartes’ claim (amplified by Spinoza) that God is “the only absolutely self-sustaining substance.”[18] This probably too hasty dismissal of German Idealism prefigures Whitehead’s later comment in Process and Reality that “the philosophy of organism is a recurrence to pre-Kantian modes of thought.”[19] In HL2, God becomes a self-creating creature like all others, differing only in aboriginality. God’s primordial nature is described as equivalent to the “ideal world of conceptual harmonization,” a divine telos that remains eternal even while it becomes variably immanent in world history as relevant to each occasion of experience.[20] His later discovery of the consequent nature of God will lead him to admit at least some approximation to absolute idealism, but he still refuses to grant God ultimacy.[21] God like all creatures remains an accident of Creativity.

Despite the remarkable theological adventurousness of Religion in the Making and his concurrent lectures captured in HL2, it appears that Whitehead had not yet fully arrived at his mature conception of God by the end of the spring 1927 semester. Whitehead scholars will know that, while John Cobb, Jr. thought the consequent nature was at least foreshadowed in Religion in the Making, Ford made the case that Whitehead does not attribute physical feeling to God until Process and Reality.[22] Does the publication of HL2 (specifically, the lectures Ford did not already have) help settle the score? In Conger’s notes from November 9, 1926, he records Whitehead affirming that God “requires all other creatures in order to exist,” and that “there is a history of the temporal world in God and vice-versa.”[23] There is at least an embryonic suggestion of a consequent nature in these statements, but as is clear from Whitehead’s reading of Religion in the Making at the end of the same class, he was still conceiving of God as necessarily “[including] all possibility of physical value conceptually”[24] [my italics]. Thus it appears that Whitehead was not yet ready to affirm that God’s nature includes a physical pole, i.e., that God is affected by physical occurrences.

The second volume of The Harvard Lectures offers more than a historical snapshot or a new opportunity for scholars to debate. It records the twentieth century’s preeminent metaphysician in his most creative phase, responding to student confusions, testing new formulations, and drawing upon everything from classical philosophy and advanced mathematics to recent developments in physics and biology on the way to a stunningly comprehensive cosmological scheme. While Scarfe’s caution about the indirect nature of these notes remains important, and while they seem unlikely to lay long-standing interpretive controversies to rest, there are many insights that can be garnered that significantly enrich our understanding of Whitehead’s project. Taking shape in these lectures is Whitehead’s account of how nature, far from being a piling up of inert particles, is a community of animate creatures engaged in the evolution of novel values. With our troubled civilization once again looking for ways to integrate scientific explanation, aesthetic attunement, and moral significance, these echoes of Whitehead’s lectures in Emerson Hall serve as a timely reminder that another mode of thought is possible.

[1] Scarfe, Process Studies 48.1 (2019).

[2] HL2, p. 391ff.

[3] HL1, p. 10.

[4] Whitehead, Process and Reality, p. 199ff.

[5] HL2, p. 9n1.

[6] HL2, p. 6.

[7] HL2, p. 196.

[8] HL2, p. 56.

[9] HL2, p. 87.

[10] HL2, p. 55.

[11] First recorded in student notes on January 8, 1925 (HL1, p. 161) and more thoroughly developed throughout HL2.

[12] Whitehead, Science and the Modern World, p. 178.

[13] HL1, p. 248.

[14] HL1, p. 250.

[15] HL2, p. 114.

[16] HL2, p. 198.

[17] HL2, p. 204.

[18] HL2, p. 205.

[19] Whitehead, Process and Reality, vi.

[20] HL2, p. 221-222.

[21] Whitehead, Process and Reality, p. xiii, 7.

[22] See Ford, The Emergence of Whitehead’s Metaphysics, p. 140ff.

[23] HL2, p. 220, 221.

[24] HL2, p. 222.

I wish you would explain process theology's afterlife(maybe you have). I read "Preaching the

Uncontrolling God"-76 sermons/essays published 3-12-24. Only 2 had more than a sentence

about afterlife, but were vague like "let's hope" then something about memories?

Please consider the above in one of your forthcoming essays. Thanks