The following is based on a revised transcript of a recent lecture for the University of Exeter.

Anyone paying attention to academic philosophy over the last decade or so will have noticed the new philosophical kid on the block. I’m talking about panpsychism. While a couple of decades ago the position would have been laughed out of court or met with an incredulous stare, nowadays an increasing number of analytic philosophers are taking panpsychism seriously. In the brief essay to follow, I’m going to try to tell you why.

First, it’s important to recognize that this position is not exactly “new.” It goes all the way back to the very origins of Western philosophy. The ancient Greek philosopher Heraclitus, for example, said not only that “all things flow,” but also that everything has an inner fire–an ever-living fire as he put it–a soul that animates it from the inside out. Really all human beings for most of history have accepted some version of this pansychist view that the world is ensouled. Sometimes anthropologists refer to it as animism. You might say panpsychism is just a more philosophical attempt to justify an animist worldview. But in the last few hundred years in European and American or generally Western societies, animism increasingly began to seem superstitious and was replaced with a kind of materialism or physicalism, which is the view that the vast majority of the universe–namely, everything outside human skulls–is just dead stuff moving through space and time according to fixed laws of physics. This view, physicalism, is now increasingly being challenged.

The reason panpsychism is being taken seriously again by academic philosophers and scientists is because of David Chalmers. Now there are other reasons, of course, that academics and scientists are turning to this somewhat odd position (“odd” relative to the materialistic common sense that has reigned in modern Western societies for a few centuries now). But David Chalmers, in looking at the study of the brain, raised a problem he called “the hard problem of consciousness.” As he put it in his famous 1995 paper in the Journal of Consciousness Studies:

Chalmers’ framing is an attempt to point out the fact that even if we understood everything there is to know about human behavior from a neurobiological point of view–understanding the functions of the brain in response to stimuli from the environment, putting that in an evolutionary context–even if we understood all of that, we could still ask the questions: Why is there anyone home inside? Why is there an experiential quality to any of that neural, neurochemical going on? Why aren’t we just zombies? There seems to be something extra left over to explain, even after all the physical stuff, all the physiological activity, has been well understood.

These are some contemporary panpsychist philosophers: from left to right, Freya Mathews, Galen Strawson, Godehard Brüntrup, Philip Goff, and Isabelle Stengers. All of them are at least sympathetic to panpsychism, if not outright defenders of the position. And these are just some of the philosophers. There are also some scientists, like Christof Koch, as well as Michael Levin. Levin, for example, has been driven to adopt a kind of panpsychism in an attempt to understand the collective intelligence of cells. We human beings are multicellular organisms, and we develop from a single fertilized egg. From Levin’s point of view, that egg is itself a kind of packet of physics and chemistry. And somehow it becomes us, it becomes our unified sense of self-consciousness. For Levin, the only way that this process could self-organized is if cells are capable of participating in the achievement of goals within what he calls a higher “morphospace” that no one cell in and of itself can understand or perceive. So there’s this capacity for cells to merge, and to generate emergent levels of conscious agency. We ourselves are an example of this emergent panpsychism.

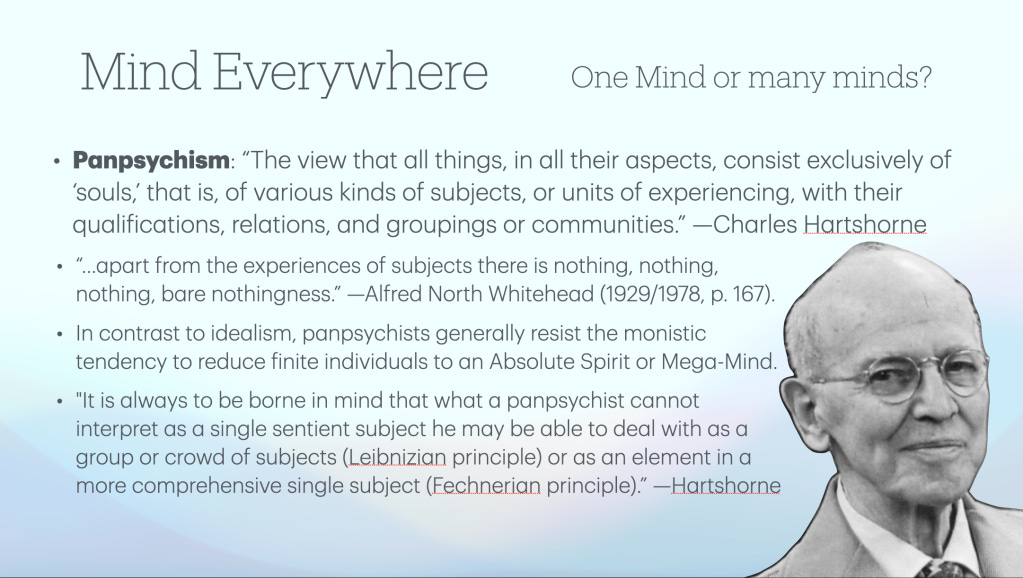

In an encyclopedia article on panpsychism published in 1950, Charles Hartshorne defines the position in the following way:

Now Hartshorne contrasts his favored version of panpsychism from other versions that he refers to as “dual aspect” approaches. This would be the idea that everything has both physical and mental properties, thus in a sense pushing dualism all the way down. Since it is unclear how such properties could causally relate, this leads to the idea of parallel tracks, mental and material, running in a pre-established harmony from the beginning of time without ever actually touching. Another approach is in terms of dual aspects of some underlying monistic stuff, a kind of “dual aspect monism.” Instead of positing two distinct kinds of reality, Hartshorne wants to just do away with mind-independent matter. Instead, he adopts Whitehead’s idea, that “apart from the experiences of subjects there is nothing, nothing, nothing–bare nothingness.” So there is no matter independent of a subject perceiving it. And even then, what is being perceived is just other objectified subjects.

Hartshorne wants to be very clear that this is not a kind of idealism. In dismissing matter as a kind of abstraction and replacing materialistic atoms with psychic atoms, Hartshorne is still a realist. He’s saying there really are other psyches out there independent of our own psyche. And so in contrast to idealism, Hartshorne wants to say that panpsychists resist this monistic tendency to dissolve finite individuals into the Absolute Mind or Mega Mind, just as much as they resist the temptation to reduce any particular level of consciousness to its subcomponents. There are many levels of mind operative in the universe, many rhythms and tempos of experience that are operating in complexly entangled ways.

A lot of people like to throw rocks at panpsychists by incredulously demanding to know if we really think that rocks can think or that rocks feel pain. In response, Hartshorne point both to Leibniz’s idea of crowds of subjects (the monadology) as well as to Fechner’s idea of larger enveloping subjects. What we think of as solid, inanimate objects–tables, chairs, rocks, mountains, and so on–they’re really aggregates of micro-subjects, and the solidity and inertness of these objects is really just a function of the aggregation and statistical cancelling out of the agency of their mini-psychic constituents. Don’t think here of smallness in size, but in intensity and depth of experience: the experience associated with animals is far more intense than that associated with the atomic elements composing mineral bodies. “Souls may be very humble sorts of entities,” as Hartshorne reminds us. From his point of view, to say “mind is everywhere” does not mean that all finite individual minds must be reduced to the One Mind. There’s elbow room in the universe for individuality, for self-creation, at various scales.

If panpsychism entails this kind of pluralistic realism, one problem that has been pointed out is the so-called combination problem: Can minds really be made of other minds? What is the psychic or mental “chemistry” that explains the way that higher minds emerge from lower minds, bigger minds from smaller minds? This problem was first pointed out by William James in his Principles of Psychology, and he revisits this problem again in A Pluralistic Universe. In short, if we think of minds in terms of the usual substance-property logic, any attempt to combine them leads only to self-contradiction. The laws of identity and non-contradiction leave only one (in James’ view) pseudo-solution: recourse to an Absolute Mind or All-Form, an infinite substance whose finite modes or each-forms are deluded by their distinctness and sick with amnesia.

Instead of mystically leaping into the Absolute, James argues that–short of forgoing the reality of individuality–the only real solution to this problem must be to let go of our desire to intellectually or logically explain in abstract concepts how minds might merge, and instead just accept our immediate experience of the fact that minds just do interpenetrate and relate with one another. James writes: “Our intelligence cannot wall itself up alive, like a pupa in its chrysalis. It must at any cost keep on speaking terms with the universe that engendered it.”

Then there is Gustav Fechner, a renown physicist and psychologist who also believed in an Earth-Soul–that all human beings and all plants and animals were many souls embedded within the mega-soul of the Earth itself. The Earth, he felt, is a kind of angelic being floating through heaven along with the other planets and stars, each conscious in its own way. He writes: “Our whole body and every organic creature body is built of cells. …The Earth… is only the greatest model and at the same time the Mother cell of all these cells.” James writes quite favorably of Fechner’s view in A Pluralistic Universe.

James recognizes how despite what abstract logic says with its watertight categorical compartments, our direct experience shows us that moments run into one another continuously, they interpenetrate:

“What in them is relation and what is matter related is hard to discern. You feel no one of them as inwardly simple, and no two as wholly without confluence where they touch. There is no datum so small as not to show this mystery, if mystery it be. The tiniest feeling that we can possibly have comes with an earlier and a later part and with a sense of their continuous procession.”

James here is describing what he elsewhere calls the “specious present”: the way in which the present moment also affords us direct intuition of the past and of the future. The present is not cut off from past and future; experience is a continuous flow, even while it also achieves individual perspectives. James’ panpsychist speculations foreshadowed another panpsychist, or panexperientialist if you prefer, undoubtedly the most systematic, speculative philosopher in the 20th century to adopt the position: Alfred North Whitehead. Like James, Whitehead affirmed that there’s both a transitional, continuous phase to experience, and there’s also, in his terms, a “concrescent” or atomistic phase.

Whitehead’s attempt to provide a new process-relational logic for this process of experience comes in the form of his idea of “concrescence.” Concrescence is the process whereby the many become one, and are increased by one. This is his attempt to save James from the charge of anti-intellectualism. James was willing to forgo logic in favor of the direct deliverances of life, an expression of his radically empirical movement towards a pluralistic, panpsychic view of the universe. Whitehead, on the other hand, sought to provide a novel logic that can account for this process so that we don’t have to appear anti-intellectual.

Whitehead’s process of concrescence describes these units of experience or “actual occasions” as having a physical pole, prehending perished objects in the past environment as objective data, and responding to them with a subjective form or some kind of emotional tonality. Then, in the mental pole, these prehensions grow together with ingressions of eternal objects or pure potentials (with many eternal objects being negatively apprehended) as they are integrated in a movement towards satisfaction. Each moment of experience is an aesthetic process of composition that builds on what came before, gathering in the many perished objects of the past, allowing those objects to grow together into a new unit of experience. A new subject is achieved, and once its satisfaction is achieved, it becomes what Whitehead calls a “superject,” which perishes, launching itself into the future to be inherited as an object by the next unit of experience, in the next subjective occurrence.

Even if panpsychism solves the hard problem of consciousness, many critics point out that it has an equally hard new problem, the combination problem. While there is no space here to go into the details, Whitehead does provide a logic of process whereby experience can be understood in a drop-like way as pulses of internally related but nonetheless individuated subjectivity. Whitehead’s process-relational panexperientialism thus dissolves the combination problem. Whitehead’s process-relational solution allows us to adopt the panpsychic view of the universe without facing the sort of problem that materialism does–namely, Why should there be consciousness at all in a physical universe?–as well as the problem of dualism, which has to do with how mind or the psychic interior dimension of reality could ever relate to matter or the exterior, physical dimension. Panpsychism is also a less inflated alternative to idealism, where everything becomes one Absolute Mind that most every finite mind somehow fails to notice–a doubly sorry state considering our seemingly partial perspectives are also supposed to be mere illusions! For idealism as much as for materialism, the individual conscious agents populating our everyday world simply should not exist.

Panpsychism is a more radically empirical alternative to these other philosophical positions. And indeed, I think the psychedelic experience, as some empirical data is already beginning to show, affords itself of the panpsychist interpretation. Mind extends far beyond just the boundaries of human skulls, even while retaining differentiated contours.When panpsychists say “mind is everywhere,” this does not mean mind is a kind of soup that we’re swimming in. Mind is individuated; it comes in the form of selves or cells. And selves as much as cells are born, live, and die in community.