Notes on Carl Jung's Psychology of the Trinity

Some reflections on the repression of the Fourth, and Rudolf Steiner's differentiation of evil into Luciferic and Ahrimanic extremes.

In part five of his essay “A Psychological Approach to the Trinity,” titled “The Problem of the Fourth,” Carl Gustav Jung turns to Christian, Gnostic, and Hermetic religious symbolism for clues about the collective psychological development of Western humanity. His aim is not to offer metaphysical disambiguations of theological dogmas but to illuminate the path toward psychological individuation and healing.

A prerequisite for Jung’s psychological analysis of the Trinity is the concept of archetypes—universal, collective symbols living in the unconscious. For Jung, dogmas like the Trinity are not mere individual projections but collective phenomena that have evolved over millennia. Such archetypes hold profound psychological significance for humanity and must be understood as expressions of a species-level process rather than isolated delusions. Speaking as a physician and a radically empirical psychologist, Jung emphasizes that nobody really knows what these psychological projections called “Christ” or “Satan” might be in themselves. All we can say is that they exist as autonomous unconscious powers, acting to shape human history at least as much as individual egos.

Jung begins his essay on the Fourth with Plato's dialogue Timaeus, which itself begins with a curious emphasis on the numbers one, two, and three, followed by the pressing question: “But where is the fourth?” Though many pre-philosophical myths feature symbols of threeness, Jung regards Plato as the first trinitarian thinker to raise the pattern into conscious reflection and subject it to logical ordering. Still, Plato remains close enough to the primal memory of the fourth to at least acknowledge the obscure absence of a crucial component in his cosmology. Plato’s preference for triads in psychology as well as cosmology contrasts with Pythagoras’ understanding of the soul as a square—a symbol of Quaternity—rather than a triangle.

Jung admits that Plato’s account of the triune World-Soul—comprising the Same, the Different, and the Mixture—at least hints at a fourth. This extra element is the “dark and difficult” form of formlessness, named the chora or receptacle by Plato. The chora provides the medium by and through which the forms can manifest, representing a necessary but elusive component of reality that both makes knowledge of the physical world possible while also itself defying rational explanation.

Jung draws an analogy between the symbol of the Quaternity and his theory of psychological functions: thinking, sensing, feeling, and intuiting. According to Jung, individuals have a dominant function, supported by two auxiliary functions, while the fourth function remains inferior and is often repressed. This repression is a necessary consequence of the development of consciousness: to fully irradiate one function is to thrust its opposite into shadow.

For instance, in Faust, Goethe's dominant functions—intuition, feeling, and sensing—are prominent, while his inferior function, thinking, manifests unconsciously through the character of Faust. Jung writes:

Although emancipation from the instincts brings a differentiation and enhancement of consciousness, it can only come about at the expense of the unconscious function, so that conscious orientation lacks that element which the inferior function could have provided.

Jung then explores the concept of evil as an autonomous psychological reality, equal in power to good. He notes that biblical texts often portray Satan and the Antichrist not merely as absences of good but as active, independent forces. He thus challenges the orthodox perspective, that evil as a mere privation or absence, and underscores its role in the process of individuation. Jung asserts that disobedience and differentiation are essential for creation. Without sin, there could be no material world and, consequently, no possibility for divine grace or salvation.

The missing fourth element, when repressed, represents the body or material reality, both often associated with the devil—“the lord of this world.” But again, this very source of resistance and incompletion in God proves crucial for individuation.

Jung interprets the Holy Spirit as a reconciler that unites the divided aspects of the Father (Son v. Satan) into a harmonious whole. The Holy Spirit becomes “the answer to the suffering in the Godhead which [Christ] personifies.” This reconciliation mirrors the psychological process of integrating the inferior function to achieve wholeness. Jung also draws parallels to the zodiacal age of Pisces, symbolizing duality—the two fishes swimming in opposite directions—and the need to transcend opposites to attain psychological resolution.

While Jung does not reference Rudolf Steiner, their accounts of evil invite comparison. Steiner differentiated evil into two adversarial forces: Lucifer and Ahriman. Lucifer represents the tempter who incites pride, excessive spirituality, and escape from the material world. Ahriman, on the other hand, embodies materialism, cold intellect, and denial of the spiritual. Steiner believes Goethe conflated Lucifer and Ahriman in the figure of Mephistopheles in Faust, and would likely see the same conflation operating in Jung. For instance, Jung claims:

The act of love embodied in Christ is counterbalanced by Lucifer's denial.

In this case, Steiner would say Jung really means Ahriman’s denial (the “doubting thought” in Ahura Mazda), not Lucifer’s (who is not the denial of the Light but its selfish over-emphasis). Putting its spiritual truth or falsity to the side, we might ask, is Steiner’s more differentiated understanding of evil of any psychological value? Might Jung’s alleged conflation be symptomatic of the very imbalance he seeks to diagnose? Perhaps confronting and integrating the shadow involves its own sort of fourfold. Let us consider a symbol.

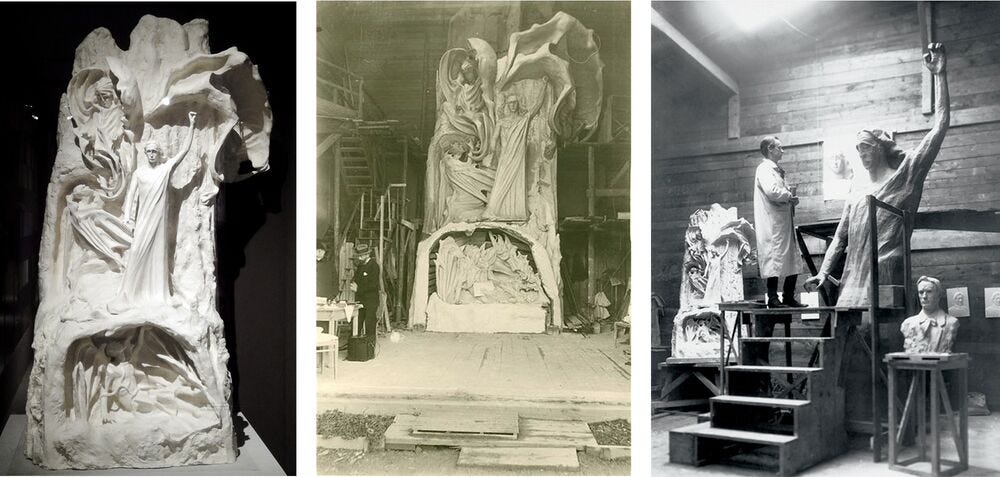

Steiner’s “Representative of Humanity” statue could be interpreted as an expression of Jung’s archetype of the Quarternity. It features Christ between Lucifer and Ahriman, with Cosmic Humor looking on above. There is an added layer of fractal complexity here: Steiner found it artistically and spiritually necessary to depict both Lucifer and Ahriman as doubles, one a picture of the being as earthly humanity encounters it and one as it exists spiritually. Lucifer’s falling spiritual form is loving grasped by Christ’s left hand, while his human form floats above Christ’s right shoulder. Ahriman’s subphysical form hollows out a cavern under Christ’s feet, while his human form kneels below Christ’s right hand.

Steiner:

In the middle of this group will stand a figure like, I would like to say, the representative of the highest humanity that could unfold on Earth. Therefore one will also be able to feel this figure of the highest human being in the development of the earth as the Christ. It will be the special task to shape this Christ figure in such a way that one will be able to see how this earthly body, in every expression, in everything about it, is spiritualised by that which has moved in from cosmic, from spiritual heights as the Christ. Through the raising of the left arm of the Christ figure, it happens that this descending entity breaks its wings. But it must not look as if the Christ were breaking the wings of this entity (Lucifer), but the whole must be artistically designed in such a way that, as the Christ raises his arm, it is already evident from the whole movement of his hand that he actually has only infinite compassion for this entity. This being, however, cannot bear what flows up through the arm and the hand; one would like to clothe its feeling in the words: I cannot bear that such purity should shine up upon me.

And on the other side the rock will be hollowed out. In this hollow is also a figure that has wings. The figure in the cave is literally clinging to the cave, you see it in chains, you see it working down there to hollow out the earth. Christ has his right hand turned downwards. Christ himself has infinite compassion for Ahriman. But Ahriman cannot bear it, he writhes in pain through that which radiates through the hand of Christ. And what radiates there causes the gold veins that are down in the rock cave to wind like cords around Ahriman's body and bind him. (Lit.:GA 159, p. 248ff)

…

The elemental being above Lucifer - the World Humor. [It] arose as one that grows out of the rock as an elemental being. This looking down over the rock with humor has a good reason. It is not at all right to want to rise into the higher worlds with mere sentimentality. If one wants to work one's way up to the higher worlds, one must not do it with mere sentimentality. This sentimentality always smacks of egoism. (Lit.:GA 181, p. 312ff)

The human being is living soul and dying body. We are the crossing of eternity and time, the bridge between heaven and earth. Despite their differing understandings of how evil may come to be personified and differentiated, both Jung and Steiner agree that evil is an integral part of the divine process, as real as good. The shadow cannot be rationalized away. But it may yet be redeemable.

Jung notes that, on the second day of Genesis, after separating the waters above from those below, God does not declare it “good” as he does the other days. This omission, Jung argues, may reflect a deep metaphysical or psychological wound in the godhead itself, with the second day symbolizing an evil splitting between higher and lower realms that has yet to be resolved.

Jung contrasts the instinctual nature of early Greek thought, exemplified by Pythagoras’ Fourth, with the emerging emphasis on the triad in Plato’s philosophy. This shift reflects a movement away from instinctual embeddedness in chthonic nature toward a more differentiated consciousness. The rise of Christianity further represents the development of consciousness separating from nature in an embrace of the spiritual. This separation has generated tremendous psychological conflicts that necessitate a reconciliation between the spiritual and the natural, the moral and the physical.

Jung remarks on the limitations of a pure spiritual faith detached from the realities of earthly existence:

This freedom is, to a large extent, a phenomenon of civilization, the lofty preoccupation of that fortunate Athenian whose lot it was not to be born a slave. We can only rise above nature if somebody else carries the weight of the earth for us. What sort of philosophy would Plato have produced had he been his own house-slave? What would the rabbi Jesus have taught if he had had to support a wife and children, if he had had to till the soil in which the bread he broke had grown, and weed the vineyard in which the wine he dispensed had ripened?

The interplay between knowledge (gnosis) and faith is another focal point in Jung’s essay. He observes that the early Church Fathers valued knowledge as essential for the growth of faith, contrary to the perceived opposition between the two. Jung conceptualizes the progression from the Father to the Son to the Holy Spirit as a psychological development from pre-personal childhood through adolescence and personal maturity into transpersonal wholeness. This journey involves sacrificing childish naiveté, confronting rational self-differentiation, and ultimately integrating with that which transcends individual ego consciousness.

He notes:

Just as the transition from the first stage to the second stage demands the sacrifice of childish dependence, so at the transition to the third stage an exclusive independence has to be relinquished.

Jung employs analogies from physics to elucidate theological concepts, suggesting that the Holy Spirit can be likened to the emergence of photons from the destruction of matter, while the Father is akin to the primordial energy forming positive and negative charges. He argues that both physics and theology rest on the same archetypal foundations rooted in the depths of the psyche.

Symbols, arising from the unconscious, are vital vehicles for individuation, even when their meanings elude rational understanding. Jung emphasizes the importance of symbols as catalysts facilitating transpersonal growth. As a product of the unconscious, a symbol cannot be “made to order as the rationalist might wish.” Living symbols arise organically and allow the ego to consciously integrate with otherwise problematic unconscious contents, but only if it is willing to open itself to the influx of the anima mundi.

Jung denounces the tendency among theologians of his day to dismiss psychological efforts to address spiritual needs. Theology, he says, often proclaims incomprehensible doctrines while demanding unattainable faith, neglecting the psychological work necessary for genuine spiritual conversion.

While Protestant traditions may struggle with this disconnect, Jung acknowledges that Catholic rituals like communion provide symbolic enactments that allow the unconscious to be more directly influenced by archetypal meanings.

But in the end, for both Jung and Steiner, what is required is that individual human beings develop the natural knowledge and moral will to go beyond good and evil. Do not worship the God-man on the cross. Carry the cross yourself. The time for integration of the opposites is always now.

"Without sin, there could be no material world and, consequently, no possibility for divine grace or salvation."

felix culpa

"This omission, Jung argues, may reflect a deep metaphysical or psychological wound in the godhead itself, with the second day symbolizing an evil splitting between higher and lower realms that has yet to be resolved."

one may explore the Kabbala idea of tzimtzum as well.

I was just reading a text by Sean McGrath on Schelling and your post came to add new ideas. Thanks!