‘No Thinker Thinks Twice’: On the Attempt to Catch Whitehead in the Act of Philosophizing

Preliminary reflections on my panel presentation for the "Whitehead at Harvard" centennial conference this Friday, September 27.

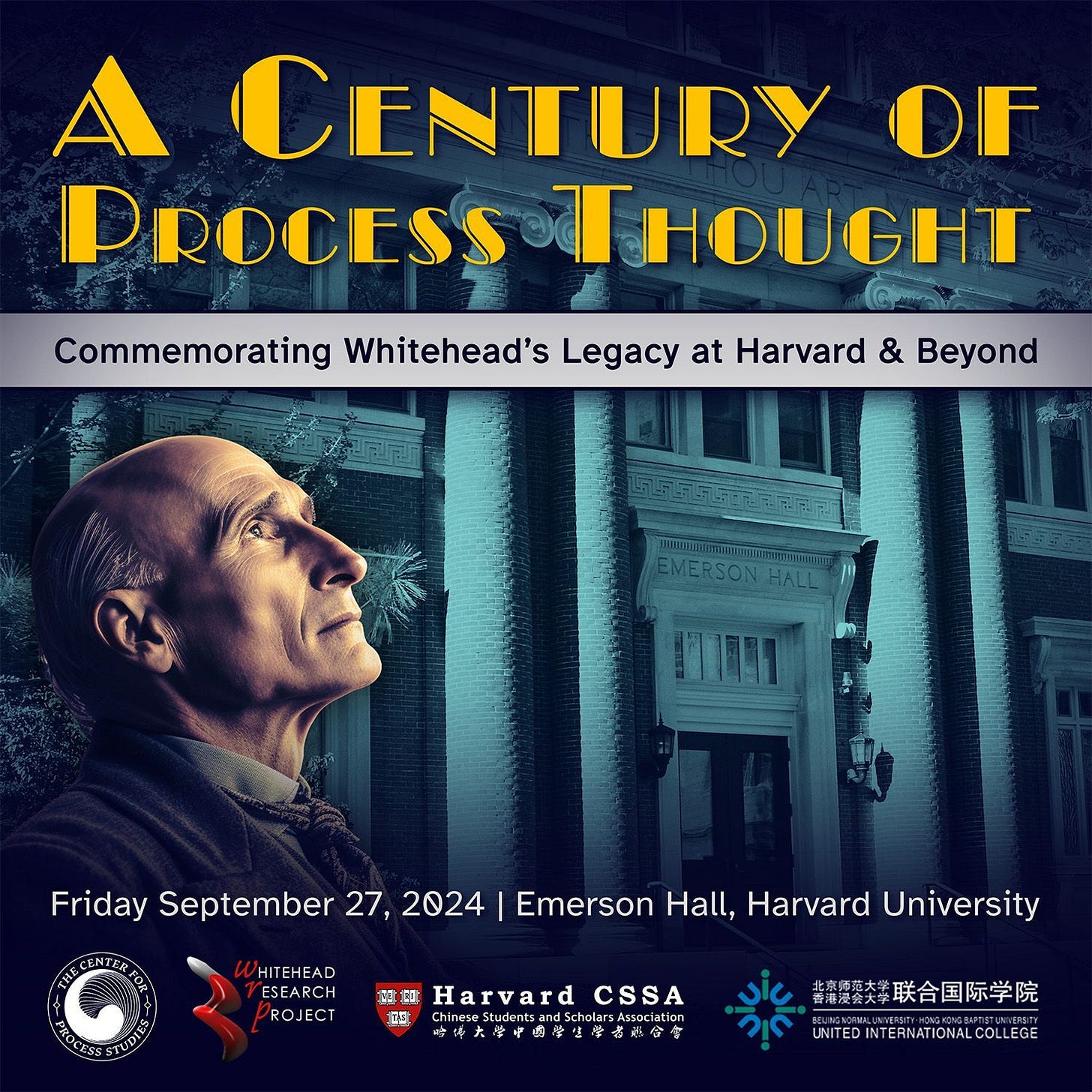

This Friday, I’ll be traveling to Harvard University for “A Century of Process Thought: Commemorating Whitehead’s Legacy at Harvard and Beyond.” The event is free to attend in-person or online (follow the link to register). The original plan had me simply chairing a panel on the development of Whitehead’s thought at Harvard. But panelist Jude Jones is no longer able to attend, so I’ve been asked to offer a few thoughts of my own. I’ve tentatively titled my remarks “‘No thinker thinks twice’: On the Attempt to Catch Whitehead in the Act of Philosophizing.” The first line is one of my favorites from Process and Reality (p. 29). Here is the context:

It is fundamental to the metaphysical doctrine of the philosophy of organism, that the notion of an actual entity as the unchanging subject of change is completely abandoned. An actual entity is at once the subject experiencing and the superject of its experiences. It is subject-superject, and neither half of this description can for a moment be lost sight of. The term ‘subject’ will be mostly employed when the actual entity is considered in respect to its own real internal constitution. But ‘subject’ is always to be construed as an abbreviation of ‘subject-superject.’ The ancient doctrine that ‘no one crosses the same river twice’ is extended. No thinker thinks twice; and, to put the matter more generally, no subject experiences twice. […] In the philosophy of organism it is not ‘substance’ which is permanent, but ‘form.’ Forms suffer changing relations; actual entities ‘perpetually perish’ subjectively, but are immortal objectively. Actuality in perishing acquires objectivity, while it loses subjective immediacy. It loses the final causation which is its internal principle of unrest, and it acquires efficient causation whereby it is a ground of obligation characterizing the creativity.

Due to the tireless work of the good folks at the Whitehead Research Project, the student notes from Whitehead’s Harvard lectures have recently been edited and published (so far, HL1 up to 1925 and HL2 up to 1927, with more volumes in the works). Whitehead scholars have thus been given the opportunity to step into his philosophical laboratory in Emerson Hall in an attempt to catch Whitehead in the act of creating his concepts. This has its own intrinsic value, of course, but personally I would want to avoid unduly dwelling on trivial questions concerning, eg, when exactly Whitehead came up with this or that new idea. More important, to my mind (and, I imagine, to Whitehead’s), is understanding the connections he was striving to articulate and why he felt they were important. Whitehead was not simply introducing new ideas, but attempting to revitalize a civilization he perceived was veering toward catastrophe already a century ago.

One of the key issues the publication of student lecture notes brought to the fore concerns the contrast between atomicity and continuity. These are abstract concepts at first glance, but how we approach their integration has profound implications for the still hot topic debate about freedom and determinism. If individuality is not realized within the continuous unfolding of nature—if everything is an unbroken, seamless flow—then concepts like “me,” “you,” or any decision that could influence the future cease to have any meaning. In such a purely continuous process, with no “elbow-room” for self-creation, individual agency evaporates (see Adventures of Ideas, p. 195).

Whitehead, though known as a process philosopher, also introduced the concept of “actual occasions,” which are discrete units of experience that arise out of and inherit an objectively immortal past, enjoy a moment of subjective immediacy, and perish into an anticipated superjective future. Actual occasions do not endure and do not recur (“societies” endure, while “eternal objects,” or “forms” in the above quote, recur). They arise and perish, embodying the entirety of the universe up to the moment of their emergence while also adding a novel perspective and value-experience to that universe. There’s significant debate among Whiteheadians about when exactly Whitehead recognized that continuity alone was insufficient and that incorporating atomicity was necessary. This recognition has far-reaching implications, not just for physics—potentially reconciling the continuity of electromagnetism and relativity theory with the apparent discontinuities of quantum physics—but also for understanding the nature of creative emergence and human freedom.

While the full-fledged concept of an “actual occasion” does not make its appearance by name until the Lowell lectures that became Science and the Modern World (1925), the idea was already sprouting in his Emerson Hall lectures by November 1924 (see HL1, p. 65). Scholars differ on whether Whitehead arrived at the idea of an atomic becoming of such occasions suddenly around March/April 1925, experiencing an “aha” moment, or whether this concept was implicitly present in his earlier work on mathematical physics. There are essentially three issues: the significance of atomicity in Whitehead's philosophy, the exact timing of his development of this idea, and whether it emerged from a sudden breakthrough or a gradual refinement. Again, the first seems most important, but the latter two issues are not irrelevant to understanding the import of the idea.

While debate on these points may appear scholastic, I must reiterate that finding the right contrast and integration of atomicity and continuity has profound implications for how we understand our human role in the universe. Our stance on this question influences our understanding of whether and how freedom and agency are possible. Let’s dig into the debate a bit.

In the book Whitehead at Harvard, 1924-1925 (2020), scholars Gary Herstein and Ronny Desmet engage in a critical dialogue about Lewis Ford’s thesis concerning Whitehead’s concept of “temporal atomism” (Ford’s term). Herstein admits that Whitehead's philosophy during his first year at Harvard was “transitional” (Whitehead at Harvard, p. 119). He complains that physicists ceased paying attention to Whitehead after he refused to “bend the knee” to Einstein’s interpretation of relativity (ibid., p. 121), implying that Whitehead’s reluctance to embrace Einstein’s idea of “curved” spacetime isolated him from the (he believes, mistaken) direction that physics ended up taking. Herstein has developed a Whitehead-inspired critique of contemporary gravitational physics in his book Whitehead and the Measurement Problem of Cosmology (2006). You can read Desmet’s review of Herstein’s book here.

Herstein is particularly critical of Ford, aiming to “put a stake through the heart of Lewis Ford’s ‘temporal atomism’ thesis” (p. 122). He questions the validity of Ford’s compositional analysis of Whitehead's published texts, a method borrowed from biblical criticism that Herstein’s argues is entirely inappropriate for understanding that varying aims of Whitehead’s published texts. Ford also relied heavily on a single set of lecture notes from philosopher William Ernest Hocking, whose notes were composed according to his own agenda and only partially covered Whitehead’s second semester in 1925 (Hocking did not attend the Fall 1924 lectures). Finally, Herstein seems to believe that Ford’s lack of mathematical facility doomed from the start any attempt to read into the true motivations for Whitehead’s ideas.

Whitehead himself acknowledged the challenges inherent in bridging philosophy and mathematics. In The Principle of Relativity (wherein he developed his own empirically equivalent tensor equations to replace Einstein’s so as to avoid the nonsensical idea of curved spacetime), he remarked, “It certainly is a nuisance for philosophers to be worried with applied mathematics, and for mathematicians to be saddled with philosophy” (p. 4). “But,” he concludes, “the difficulty is inherent in the subject matter.” Herstein contrasts this with the tendency of contemporary physicists to focus on “clever mathematical models” rather than the “conceptual physics” that Whitehead pursued in his books and Harvard lectures. Whitehead quips that he cannot go along with the “scientific Bolshevists” who were then too willing to accept utterly contradictory implications of their mathematical models, some of which affirmed waves as fundamental, while others affirmed corpuscles as such. Bell writes in his lecture notes that “Whitehead is too much of a rationalist to acquiesce in that” (HL1, p. 12).

Herstein likens Whitehead’s students’ lecture notes to a “guided tour” into Whitehead's scientific ideas (Whitehead at Harvard, p. 127). George Lucas, another scholar, refers to Emerson Hall—the venue of these lectures—as “Whitehead's laboratory” (ibid, p. 333), underscoring the experimental and exploratory nature of his work during this period. But on his reading, Herstein sees no evidence in the first year of lecture notes for any conceptual discovery on Whitehead’s part that would introduce the idea of any atomic becoming alongside the apparent continuity of spacetime.

Contrasting with Herstein’s critique of Ford’s temporal atomism thesis, Ronny Desmet offers a different perspective on Whitehead’s philosophical development. Desmet argues that when Whitehead encountered new insights prompting changes in his tentative metaphysical synthesis, he did not abandon his preliminary ideas. Instead, he engaged in a careful reconceptualization to integrate the new insights without losing the value of his existing framework (p. 132-133). Here we can see how Whitehead’s own process of philosophical discovery mirrors his account of the process of the concrescence of an actual occasion: just as each newly arising occasion must inherit its past as “ground of obligation characterizing the creativity” (Process and Reality, p. 29), Whitehead found it necessary to avoid demolishing the conceptual foundation he had already laid, choosing instead to remodel and redesign in light of any inconsistencies in pursuit of an always tentative sense of harmonious satisfaction. Even though “no thinker thinks twice,” conceptual coherence and experiential adequacy requires that we find some way of maintaining continuity with our past thoughts. Whitehead already emphasizes in his early lectures that process realizes values through transition, but beyond mere change, there must be retention or recurrence of value. This idea foreshadows his later assertion in Process and Reality that time is not only irreversible but also cumulative (Process and Reality, p. 237-8). This again resonates with Whitehead’s philosophical method. Philosophy, for Whitehead, is an organic process of growth where earlier stages may be reinterpreted and even repurposed, but not discarded. This method is evident not only in the development of his own ideas, but in his generous treatment of the history of philosophy.

While the change may not have been as dramatic as Ford claimed, Desmet lays out the evidence that Whitehead did indeed put new emphasis on atomicity in the second semester of his HL1 lectures (p. 136). For my part, I find the evidence of a shift rather convincing and worry that, when assessing Ford’s account of the emergence of temporal atomicity, Herstein has let his personal animosity (justified or not) confuse the issue (see also Herstein and coauthor Randall Auxier’s treatment of Ford’s thesis in their book Quantum of Explanation, where they claim their animus toward Ford’s thesis does not entail any animus toward the man). It may be that Ford’s methods and arguments were faulty, but now that we have a fuller picture of the ideas Whitehead was working out during his first semester at Harvard, it is hard to deny the general accuracy of the thesis that he did, in fact, introduce the idea of an atomicity of becoming during the spring semester of 1925.

Desmet notes that in the fall semester of the 1924-1925 academic year, Whitehead was not yet convinced of the atomicity of becoming. In October 1924, Whitehead is recorded as saying, “Reality is a flux, a process, a continuity of becoming. The continuity of flux exhibits atomic structures as imbedded in itself” (p. 142; HL1, 417). This indicates that, at that time, Whitehead saw atomic structures as embroidery within a continuous process (eg, as standing waves in the vibratory continuum), rather than as discrete units of becoming.

Desmet further highlights a shift in Whitehead’s thinking by comparing earlier and later works. In The Concept of Nature (1920), Whitehead wrote, “there is no atomic structure of durations” (p. 144; CN, 59). However, by the time he published Science and the Modern World (1925), he introduces the idea that the process of becoming is a “sheer succession of epochal durations” (SMW, p. 125). This evolution suggests a growing appreciation for the importance of the atomicity of becoming, which is irreducible to the continuity of the electromagnetic field or the spacetime continuum.

By his second semester at Harvard, Desmet notes a significant change. By late March 1925, Whitehead asserts that the process of becoming real does not occur within the field of extension and is indivisible—even if, once realized, it occupies a region in the field of extension and is divisible. He explicitly states that “process must be atomic” (HL1, p. 309), that “generation is atomic” (HL1, p. 311), and that an “atomic theory of generation is needed” (HL1, p. 506). These declarations mark a clear shift toward embracing temporal atomicity, and point toward his later elaboration of the method of genetic analysis and a theory of concrescence in Process and Reality.

Desmet contends that the primary reason Whitehead introduces the atomicity of becoming is his commitment to the irreversibility of becoming, rather than influences from quantum physics. While extension alone does not indicate the directionality of time, the cumulative nature of epochal occasions establishes a forward-moving creative advance. This emphasis on the directionality and irreversibility of time is crucial to Whitehead's mature philosophy.

In a follow-up response, Herstein meets Desmet with incredulity, focusing once again on critiquing Ford’s methodological approach rather than directly addressing the evidence presented from the lecture notes. He points out that “advanced mathematical facility is not widespread among Whitehead scholars” (p. 191), again suggesting that a lack of mathematical understanding may contribute to misinterpretations of Whitehead’s ideas. While he is probably right about Whitehead scholars (eg, I have not studied the calculus much less linear algebra), I remain skeptical this is entirely relevant to the point at issue, especially considering Herstein’s own emphasis on the importance of the undervalued conceptual aspects of physics. Desmet argues that the core issue is not Ford’s method but whether Whitehead developed a new concept during his second semester at Harvard—a point supported by the lecture notes themselves.

In examining Chapter 3 of Ford’s The Emergence of Whitehead’s Metaphysics, titled “The Emergence of Temporal Atomicity,” I found a few gems worth sharing. One of the issues at stake in the atomicity/continuity contrast is the extent to which Whitehead’s process philosophy is finally monistic or pluralistic in orientation. Ford argues that “mutually internal relations and monism go hand in hand, as do asymmetrical relations and qualified pluralism” (p. 57). While Whitehead eventually settles on the latter position of qualified pluralism, there are sentences in Science and the Modern World that suggest a more Spinozistic or monist position. In line with Desmet’s argument that it was the asymmetry of time that most influenced Whitehead to adopt the epochal theory, Ford emphasizes how temporal atomism expresses Whitehead’s novel integrative solution to the debate about internal and external relations: each epochal creature or actual occasion of experience is internally related to its past, but externally related to the possibilities available for its future actualization. Further, in the present moment, the concrescence of each actual occasion unfolds in causal independence of all other occasions, thus giving each occasion “elbow-room” for self-creation (Adventures of Ideas, p. 195). This allows actual occasions to remain in conformal physical relation to the objectified past while also leaving open the possibility for conceptual contrasts and innovations. Ford admits that if “temporal atomism” is a mistaken or insufficiently qualified doctrine, then Whitehead may not have made any significant discovery. Yet, for Whitehead, the epochal nature of becoming functioned as a major discovery with profound implications for his philosophical outlook. Ford clarifies that in using the term “discovery,” he refers primarily to its psychological meaning, leaving the question of its ultimate truth open (p. 64).

I would say Ford’s argument needs only minor qualification, since there is evidence already in Whitehead’s first few lectures in September 1924 that he was anticipating the need for some reconciliation between atomicity and continuity. He observes that continuity and atomicity have “maintained [a] very equal duel through [the] history of human thought,” and he believes that neither can be dismissed. Importantly, Whitehead distinguishes atomicity (or indivisibility) from discontinuity (p. 6). On his account of processual atomism, where actualizing occasions remain internally related to those already actualized, there can still be a becoming of continuity even if a continuity of becoming is ruled out (see Process and Reality, p. 35).

Whitehead aims to reconcile the continuity of the electromagnetic field with the apparent discontinuity observed in quantum phenomena. He proposes that by reinterpreting discontinuity as atomicity—understood as indivisibility rather than fragmentation—the two can be harmonized. This approach allows for a continuous field of potentialities that is nonetheless comprised of indivisible units of becoming, or actual occasions. Whitehead thus manages to integrate otherwise disparate scientific observations, mathematical models, philosophical presuppositions, and common sense experiences into one rationally coherent and empirically adequate cosmological scheme.

In conclusion, the debate between Herstein and Desmet centers on the emergence and significance of temporal atomicity in Whitehead’s philosophy during his Harvard years. Desmet provides compelling evidence from Whitehead’s own lecture notes that indicates a clear development toward embracing the atomicity of becoming in his second semester at Harvard. Herstein, while critical of Ford’s methodologies, does not directly address the evidence of this philosophical shift. Despite methodological disagreements and personal tensions, the lecture notes suggest that Whitehead underwent a significant transformation in his thinking, integrating the concept of atomicity to account for the irreversibility and cumulative nature of time—a cornerstone of his later work that proves essential for philosophically justifying not only real evolutionary creativity but the reality of human freedom.

Further, assessing the genesis of Whitehead’s ideas allows us to appreciate how deeply the categorical content of his mature metaphysical scheme reflects his own, open-ended method of discovery. Already in his second lecture as a Harvard philosophy professor, he emphasizes the importance of thinking in terms of contrasts rather than positioning ideas as in irrevocable conflict with one another. In Process and Reality, he bestows the honor of the eighth category of existence upon Contrasts, “or Modes of Synthesis of Entities in one Prehension, or Patterned Entities,” adding that this category “includes an indefinite progression of categories,” (p. 22) thus explicitly constructing his categoreal scheme as an adventure of ideas open to future redesign.

Below I am sharing Iain McGilchrist's comment on this post over on my blog (https://footnotes2plato.com/2024/09/23/no-thinker-thinks-twice-on-the-attempt-to-catch-whitehead-in-the-act-of-philosophizing/#comment-148002):

McGilchrist:

"Thank you for your recent series of insights into Whitehead, Matt. As you know this necessity of both separation/differentiation and continuity/unity together is a theme explored throughout The Matter with Things. If you have a copy to hand, I wondered if you found my reflections (pp 833-6) on the work of the physicist Mike Abramowitz interesting in this regard? I think his distinction between the architective and connective is thought-provoking. -Iain"

-------

My reply:

"Iain, thank you for pointing out these passages on Abramowitz’s distinction between architective and connective interactions. I was already sensing the resonance as I read the first two paragraphs in these pages of TMWT above your comment that: “I cannot help seeing a similarity here with Whitehead’s idea that potential ‘plays with’ – further creates by responding positively to – whatever it is that actualisation provides.” That is exactly right, since Whitehead insists that potentiality is continuous while actuality is “incurably atomic,” though not in the substantial particle sense of “atom” as materialists typically mean it, but in the in fact more literal sense of “a-tomos” or uncuttable/indivisible. Actuality comes in holistic pulses, integrative achievements of wholeness that unify the universe into a unique recapitulation of itself. His “atoms” or actual occasions do not break the flow but contribute to its creative unfolding by allowing for the decisive ingression of alternatives not already found in the past.

That said, there are some differences between Whitehead’s actual occasions and Abramowitz’s architectivities. Abramowitz appears to be speaking more in physical than metaphysical terms about what Whitehead would call enduring entities or “societies” that repeat a definite characteristic through various occasions of their life-history. A particular molecular compound, for instance, would be an enduring society. Even though Whitehead’s actual occasions are said not to change or move (they arise and perish into objective immortality to be inherited by the next concrescent occasion), they are each a duration or becoming, a non-temporal (ie, not measurable by clocks) process of integration that only subsequently, upon achieving satisfaction, becomes part of a causal network of relations constitutive of measurable space-time.

Aside from this minor difference, Whitehead would certainly affirm that energetic vibration is primordial in nature, not stasis or rest. He even goes so far as to deny any meaning to the concept of “empty space,” since there is no space not already pervaded by energetic activity.

I also find Abramowitz’s comments about scale fascinating (architective interactions being evident only from molecules to planets, whereas connective interactions are pervasive). I am reminded of the relative merits of plasma cosmology versus the still dominant focus on gravitation, where point-instants of mass are given organizational priority while the electromagnetic fields and filaments clearly observed to connect galaxy clusters across hundreds of lightyears are ignored or not thought to play a significant role in cosmic evolution."

Thank you Matt. The expanded concept of the A-tom that ANW evolves must, in order to be real, be known clairvoyantly. Or else it will remain still another restless abstraction. Is Harvard ready to hear about Steiner clairvoyance? I hope so 😁. Break a leg 👍